Today's post is one that's been months in the making. It originally started as one that only covers a single problem, but quickly branched off as I delved deep into dozens of papers and videos, just with more and more questions coming up. We're going to be discussing one of the oldest mixed studies of algebra and geometry: dynamical systems. Today's post is going to be a long one, but should have a fair number of fun visuals to keep it worth the scroll. This is really two, maybe three posts in one, so I recommend reading this with breaks at each header as to make it less overwhelming.

To begin, let's look at a type of problem you might have experienced before, rather than have read formally: billiard problems.

For the best experience, avoid reading this in Safari; most other browsers should work and load the visuals correctly, but Safari breaks rendering a few of them.

Ricochets and Rebounds

If you have ever played pool, or even laser tag, you might already be familiar with billiard problems. If you have a billiard ball you want to land in a pocket, but there are other balls in your way, where on the side of the pool table do you want to bounce your ball to land in the pocket? Alternatively, if you have a laser gun and an opponent by a mirror, where do you want to aim your laser to hit your opponent? To reduce this problem further (and for future reference), if you have a laser, a target, and a wall, where do you want to aim the laser to hit the target?

Can you make the light hit the target? The light automatically follows your cursor, but you can press the 1 key on your keyboard to lock the angle. Try dragging the points for different problem setups.

We covered how to solve this exact problem in a previous post, which also shows how light reflects and bounces (which is what we'll be using today). To recap that post:

- Our laser/billiards bounces must follow the Law of Reflection: the angle the laser strikes the mirror is the same angle it reflects.

- To solve for where to bounce the light off the wall, we create a "mirror world" to find the reflection point.

The idea is to reflect our target over the wall, draw a straight line from our laser to the reflected target, and the intersection point is the point of reflection. This seems arbitrary, but there's a good reason for it: the angle that our straight line creates in the "mirror world" is equal to the incident angle, and therefore ensures the angle the light bounces off at in the normal world is equal. I recommend following through with the previous post for a more on this, but the following demonstration should suffice.

We reflect our target over the wall, and draw a line between the light and that reflection. Can you see why this finds us our desired reflection point?

Simple enough, but this reflection technique is an invaluable tool for solving these types of problems, so put a pin in that for later. But now, let's look at a problem that throws that very easy technique out of the window.

Alhazen's Circular Mirror

Dynamical systems have been studied since forever at this point. One of the oldest (hard) billiard problems comes from Ptolemy 150 AD:

If you have a candle and a circular mirror, where on the wall do you have to aim to hit a target?

This problem plagued the Greeks for centuries, primarily since they tried to solve this with their typical ruler-and-compass constructions. Dr. Peter Neumann proved that this is an impossible task, but other solutions and proofs have arisen over the years by some of the most famous mathematicians including Huygens and l'Hôpital. The problem was named after Abu Ali al Hassan ibn al Hassan ibn Alhaitham, later retroactively given the mononym Alhazen, who discussed this in book Optics around the 10th century.

Now, with the same light and target, can you hit the target? Drag and drop points for different problem setups; if you want to lock the light's direction, hit the 2 key.

First, let's clear some details up.

- To make sense of a curved mirror, the reflection acts according to the tangent line at the point of reflection. So, you can think of the curved mirror as made up of infinite, infinitesimal straight-walled mirrors.

- The light is a pure ray like a laser. No point source or beams to get cheap answers like, "If I stand about here, some of the light will reflect on the target." This is a laser beam that can only blind us if it directly hits us.

- In a similar manner to the light assumption, the target has been reduced a to 0-dimensional point. The light must hit the target exactly in our solution.

- And, importantly, we assume a solution exists. If the light and target are on opposite sides of the circle, clearly no reflection will make it. So, to simplify, we'll just assume that they are in positions with a possible reflection point.

Before I show you my solution to the problem, I suggest you try this problem for yourself. This is one of the few, very simple-to-state problems that has caused me a lot of trouble deciphering a clean solution for it. Mathematicians have developed quite the dictionary to solve this one problem which we'll discuss a bit at the end, but only one way has appeared the most elegant (in the most stretched definition) to me.

Clutch Complex Contours

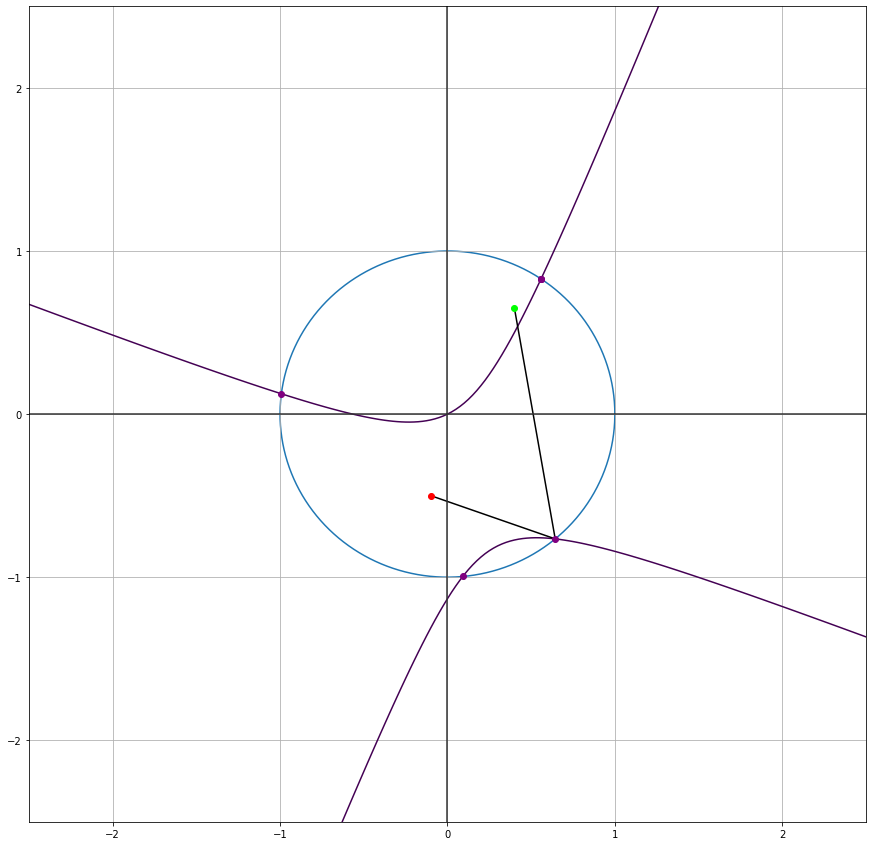

The way I solved this problem was with the magnificence of complex numbers. Let's center our circular mirror as the unit circle $Ø$ at the origin $O$, and let's call the light and target $\color{red}{a}$ and $\color{green}{b}$ (if your circular mirror is not of radius 1, just scale all coordinates appropriately to make it so). We want to solve for the point $\color{purple}{z}$ on the mirror such that $\angle azO = \angle Ozb$.

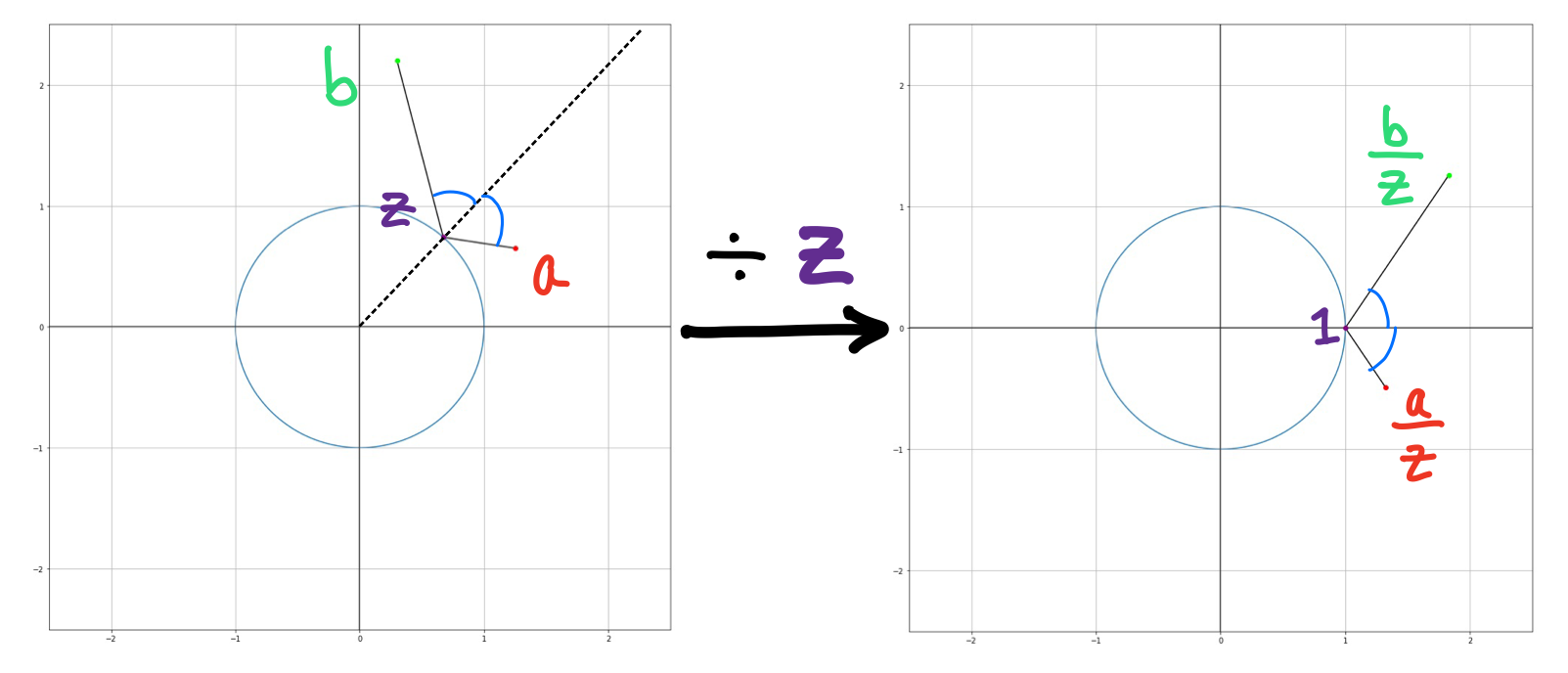

The path our light takes can be modelled in two segments: from the candle $a$ to the mirror $z$ as $a-z$, and then from the mirror to the target as $b-z$ (you'll see why we pick these directions later). To make our lives easier, let's rotate our whole setup so that the mirror reflection point occurs at $z=1+0i$ by dividing our whole setup by $z$. So right now, we have two vectors representing our reflected ray of light as $\frac{a-z}{z}$ and $\frac{b-z}{z}$ (if you're not completely familiar with the geometry of complex numbers and why this division tactic works, here's a good introductory video).

Here we have the light at $\color{red}{a}$ and the target at $\color{green}{b}$ at some arbitrary spots, with a theoretical solution at $\color{purple}{z}$. Since we don't want to work with some random tilted axis, we divide everything by $\color{purple}{z}$ to so that our set up is centered around the real axis with $\color{purple}{z} = 1$.

Since our vectors are now symmetrical about the real axis, we know that $\arg(\frac{a-z}{z}) = -\arg(\frac{b-z}{z})$ as the angle of reflection must be equal angle to the angle of incidence (see this previous post for a proof).

Ok, so why is any of this helpful? Just as we divided by two complex numbers to subtract the angles of their vectors, we can multiply them to add them together. If we multiply $(\frac{a-z}{z})(\frac{b-z}{z})$, we get that their angles sum to 0 since their arguments are opposite! If the argument of the product is 0, that means that it lies on the real axis, and therefore is a real number! We can then extract that

where $\operatorname{Im}(c)$ denotes the imaginary part of a complex number $c$. Noting that $\color{purple}{z} \cdot \overline{\color{purple}{z}} = 1$ we can further simplify this equation.

$\large{\operatorname{Im}((ab)\overline{z}^2) = \operatorname{Im}((a+b)\overline{z})}$

This might not seem like much, this describes all possible points $\color{purple}{z}$ our reflection point can lie on! Let $\color{purple}{z} = x + yi$, $\color{red}{a} \color{green}{b} = p + qi$, and $\color{red}{a} + \color{green}{b} = r + si$, and we can rewrite our equation in terms of cartesian coordinates $(x,y)$.

$\large{q(x^2 - y^2) - 2pxy = sx - ry}$

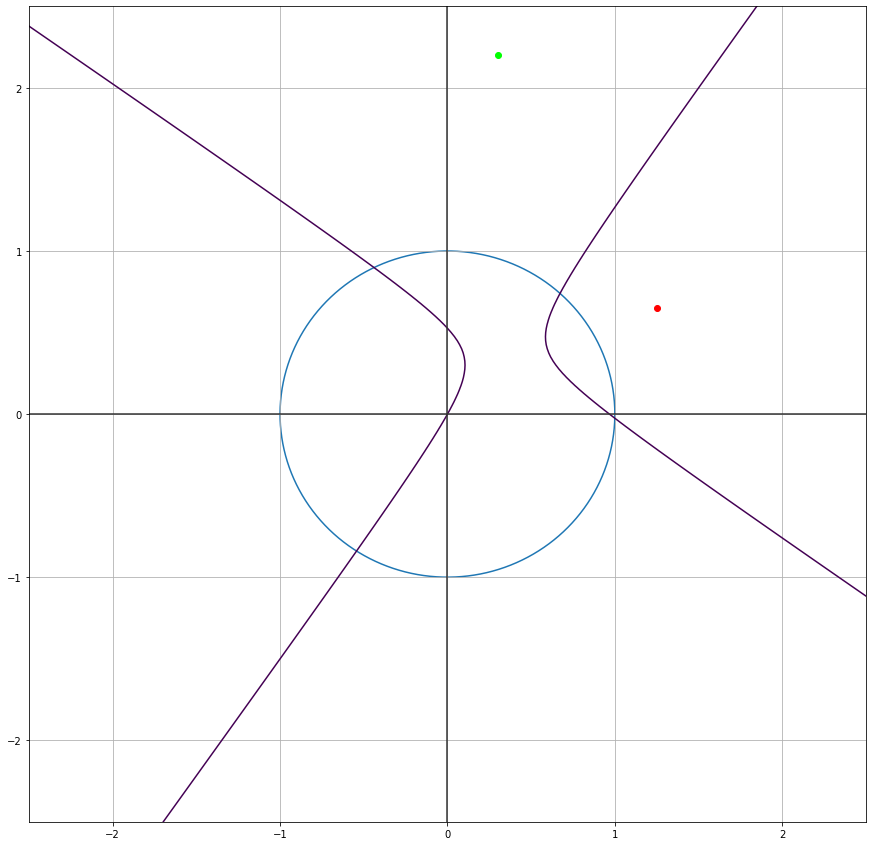

This is an equation for a hyperbola! And since we want $\color{purple}{z}$ to lie on the circumference of our spherical mirror, the point $(x,y)$ must also be a solution to $x^2+y^2 = 1$ to lie on the unit circle as well. To find where our desired $\color{purple}{z}$ is, we just need to find the intersection between this hyperbola and the unit circle.

Given our previous light and target positions, we get this specific hyperbola which intersects our mirror in 4 locations, giving 4 possible reflection points. How can we compute their coordinates, and find the correct point?

It's no coincidence that this problem involves finding the intersection between a circle and a hyperbola. While yes, all of our complex number algebra does the job, there's a purely geometrical way of coming to the same conclusion involving isogonal conjugates. I wasn't very familiar with them, so I decided to present the complex number approach instead.

You could try and solve this system of equations, but the nature of the conic sections make it a pretty tedious and gross task. Fortunately, we can actually reduce this sytem of 2 simultaneous equations to a single polynomial! Going back to one of our previous equations:

The important thing to note is that we have a complex number whose imaginary component is equal to 0. This means that this expression is equal to its conjugate, since there is no imaginary component to flip the sign of: $x + 0i = x - 0i = x$.

Again noting that $\color{purple}{z} \cdot \overline{\color{purple}{z}} = 1$, we can multiply both sides by $\color{purple}{z}^2$ to get that

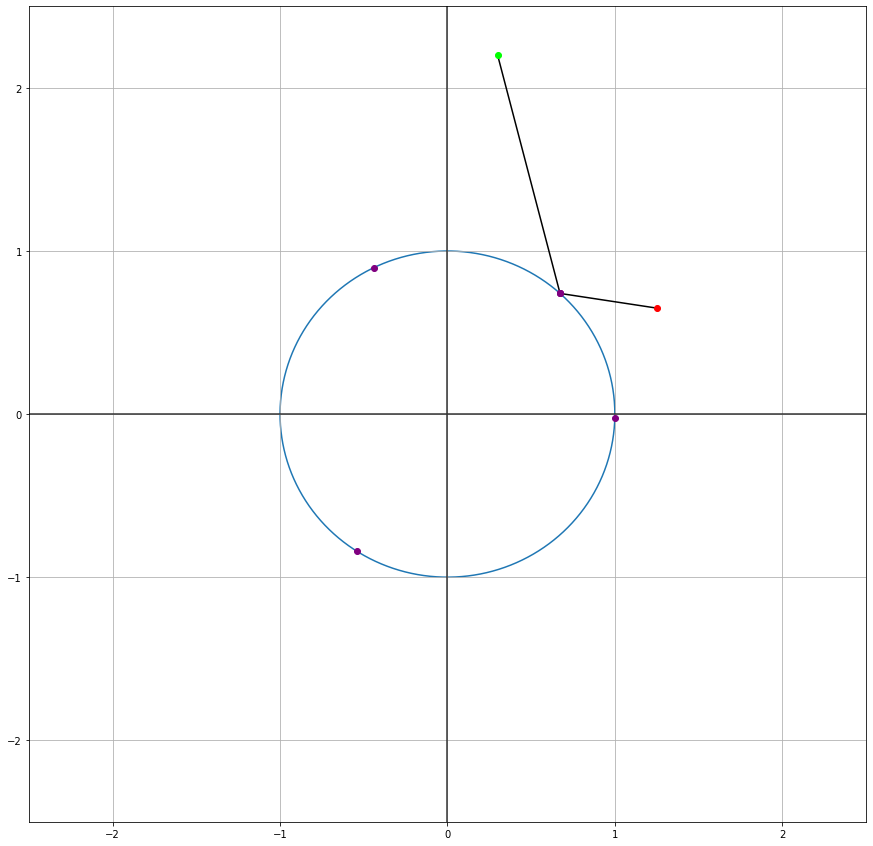

All we need are the complex solutions $\color{purple}{z}$, and since this a quartic equation, we technically have a closed form solution. Once we have the coordinates of our reflection points, all we do is graph $(\operatorname{Re}(\color{purple}{z}), \operatorname{Im}(\color{purple}{z}))$, and we are done.

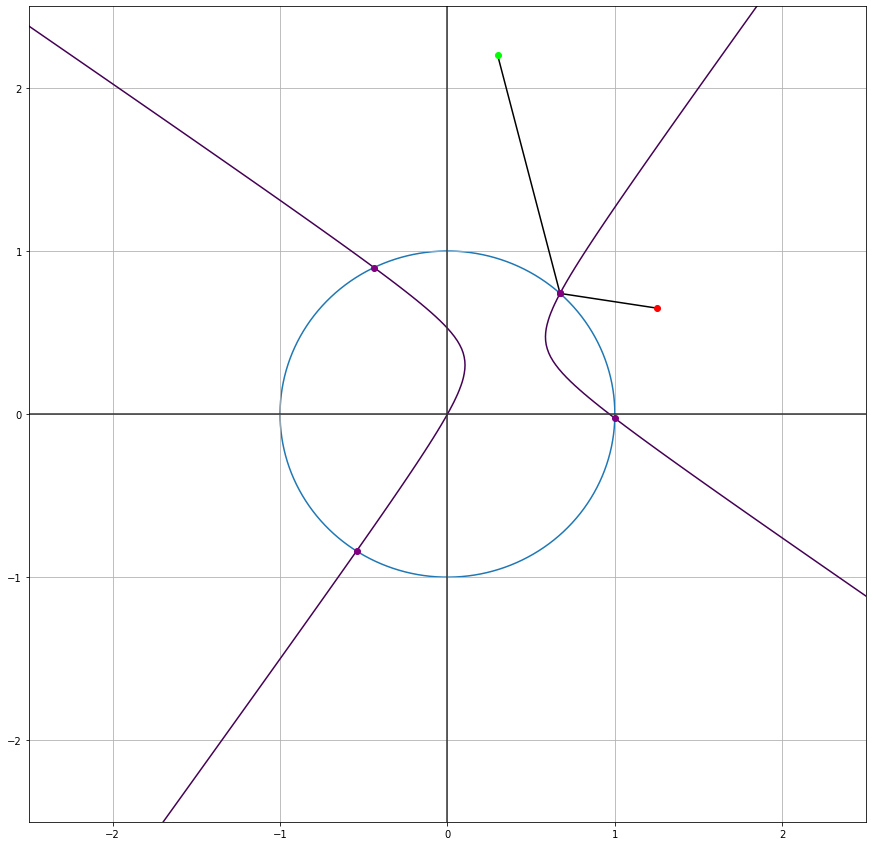

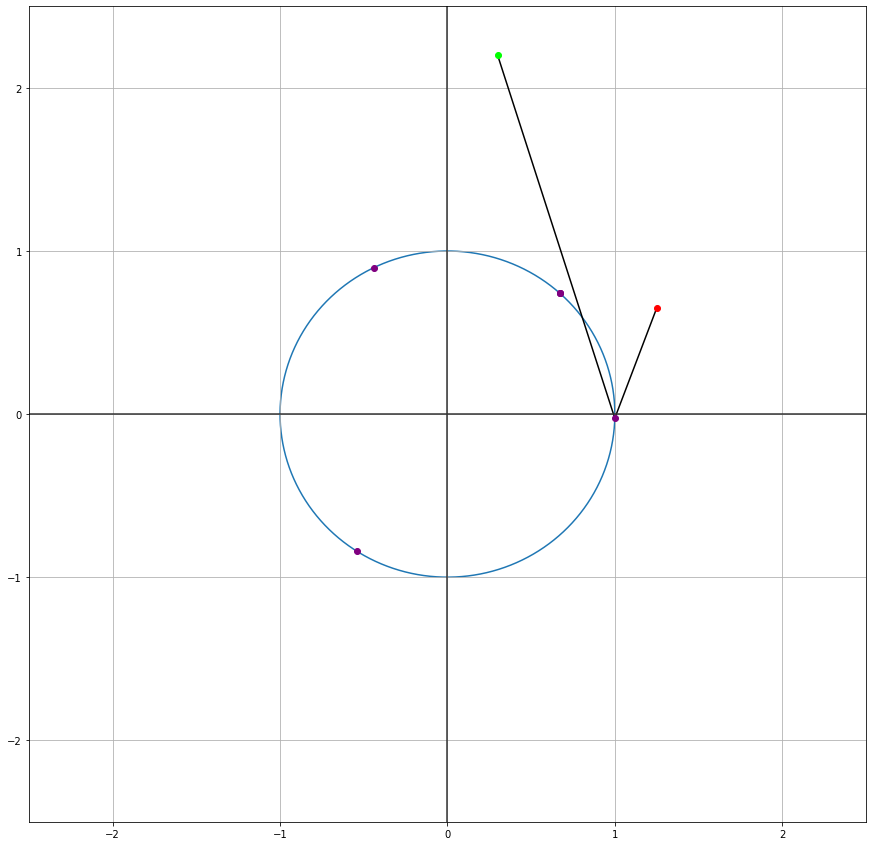

Our complex quartic generates 4 possible solutions for $\color{purple}{z}$, all on the unit circle.

If these points look familiar, they should: they are precisely the points our hyperbola predicted before!

While not ideal to compute, our hyperbola did in fact find the same potential solutions.

Also, notice how we only used information about where the supposed solution $\color{purple}{z}$ to find our quartic; we never specified any conditions for where the light $\color{red}{a}$ or target $\color{green}{b}$ had to be! This means we can have our light and target on the inside of our circular mirror and find points that satisfy the Law of Reflection.

A valid bounce inside a circular mirror.

The best part is, all 4 of the possible solutions our quartic and hyperbola find are valid! No need to worry about the laser clipping through the mirror randomly; it all works out.

While we solved the problem, there are a few details to address that are not completely obvious about this approach using complex numbers.

The Core 4

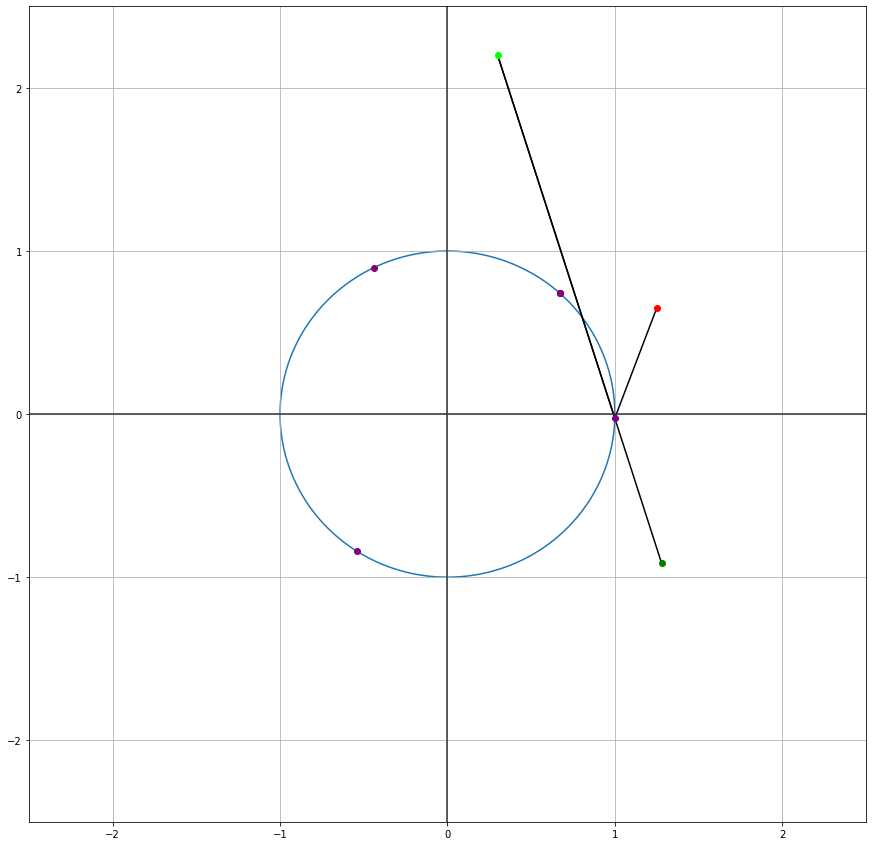

Why are there 4 "solutions" according to our polynomial? Being a quartic equation, 4 complex solutions isn't unexpected, but they don't seem to have any physical significance for our bouncing laser. Obviously, only one looks like it can reflect our points correctly; how can this be considered a viable spot to aim your laser?

A supposed "solution" our quartic generates, despite the fact the laser has to phase through the mirror on its way to the target.

No mirror bounces like that, let alone allow the laser to move straight through it. Moreover, our Law of Reflection looks completely broken, too. What's happening here?

It lies in the direction of our vectors. Watch what happens as I extend the line segment from the target to the "solution".

If we extend the ray from the target to the "solution", we can get a "mirrored target", kind of like what we did for the straight wall case.

If we extend the ray, then it's clear that the Law of Reflection is satisfied, and this is true for the 3 other supposed "solutions": every "bad" reflection point is correct if the rays are extended far enough. So the 4 "solutions" correspond with how are vectors are lined up, since if we change the direction of our light bouncing we can get different points where the Law of Reflection is satisfied.

That doesn't answer, though, how we know which point to pick as the "correct" reflection point? If you read the previous post on retroreflectors, then you know light takes the fastest and (only in this case) shortest path. So, we just pick the point where the total distance of the light's path is minimized: $\min(|\color{purple}{z} - \color{red}{a}| + |\color{purple}{z} - \color{green}{b}|)$

To be (on the circle), or not to be (on the circle)

Some of you might be wondering why this should produce any solutions on the unit circle—let alone 4 at that. That is in part by the property we have mentioned a few times: $\color{purple}{z} \cdot \overline{\color{purple}{z}} = 1$. If the geometry of this isn't obvious to you with the rotations and scalings, we can turn this into Cartesian coordinates by setting $\color{purple}{z}=x+yi$, we get that

$\large{x^2 + y^2 = 1}$

Which is precisely the equation for the unit circle. The property that $\color{purple}{z} \cdot \overline{\color{purple}{z}} = 1$ forces $z$ to be on the unit circle.

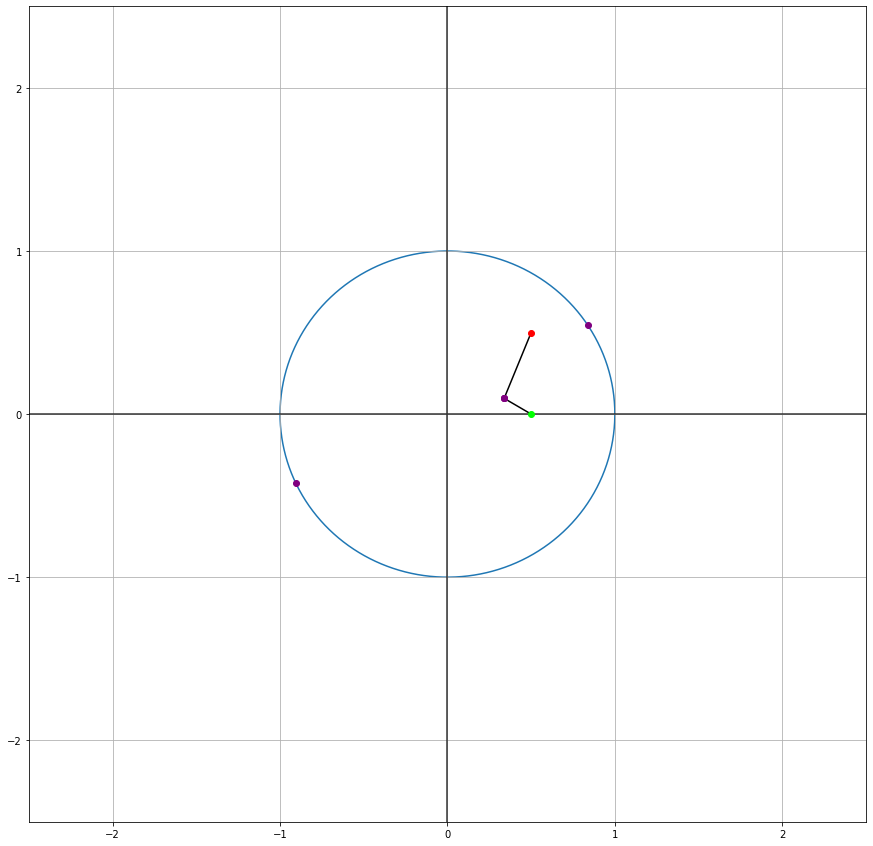

…for the most part. The proof I've highlighted is adapted from this paper. As it shows, if you have the light at $\color{red}{a}=.5+.5i$ and a target at $\color{green}{b}=.5+0i$, two of the supposed solutions for $\color{purple}{z}$ are completely off the unit circle.

When $\color{red}{a}=.5+.5i$ and $\color{green}{b}=.5+0i$, one supposed reflection point is on the inside of the circle, and the other is so far outside of the circle its offscreen.

I'm not totally sure why this happens, but the previously linked paper proves that at least two of the generated solutions must be on the unit circle.

If you want to look at this problem more, there is also an algebraic solution, here there are ideas involving tangent ellipses in this paper, and there's even an approach discussed in Dorrie's 100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics. These would be my recommended starting points. For even more depth, this is a solution involving origami (yes, the paper folding) and here's the same problem in hyperbolic space.

Now that we've seen where billiard problems started, let's see how far they've come with the main focus of today's post.

Get Down Mr. President!

You and an assassin are trapped in a square room. With a single bullet, the assassin wants to do everything he can to take you out without wasting his shot. You, however, came prepared and hired a bodyguard to prevent direct line of sight between you and the assassin. But remember, you're trapped in a room. Without hesitation, the assassin flicks a shot to the side and ricochets off the wall and grazes your arm, avoiding the bodyguard completely. You might have been lucky this time, but who knows what happens next.

If you (target) and an assassin are placed in a square room, can you hire a finite number of bodyguards to prevent any shot from hitting you (including ricochets)?

At first glance, this might seem absurd. There are an infinite number of ways for the assassin to line up and bounce his shot, so how can anything less than an infinite number of bodyguards suffice? As one might anticipate, this wouldn't be a blog post if it didn't have an incredible answer.

Can you hit the target with the assassin's shot despite the bodyguards? Drag the assassin and target points to move them, and press the 3 key to lock the angle.

It's no coincidence I placed the bodyguards where I did in the above widget; not only does a finite number of bodyguards make do, you can prove you only need to hire 16 to ensure 100% protection!

I first found this problem through Tai-Danae Bradley's video and post, where she writes up the proof very well on her own. It was this problem that inspired me to look for other problems to extend this post, and moreover it was a fun programming challenge. Here, I want to outline the proof with the key insights Bradley utilizes, as well as pose a few other questions of my own.

Just as we did before, let's clarify some problem details:

- Just like before, the assassin's bullet is a pure ray, and the target has been reduced a to 0-dimensional point.

- Now, though, we have bodyguards, which are 0-dimensional points as well; if they are going to protect the target, they have to fully take the hit.

- Lastly, just to make it clear, this is a perfectly square room and the bullet ricochets at exact angles off the walls, so the assassin's shot can bounce forever if needed to hit its mark.

The Tiling Torus

Let's look at an easy case: what if the assassin can only reflect off the left wall? Since this is a square room with straight walls, we can use our reflection trick from before. Now, though, we have to analyze the target's position in space relative to the room.

By reflecting the room, we create a "mirrored world" to track our reflection.

I've color-coded the left, right, top, and bottom walls to be yellow, gray, magenta, and cyan respectively. The reason if we want to track the target's location within the room even after the reflection, we have to reflect the room itself too, creating an actual "mirror world" that I referred to earlier.

Ok, so that isn't too different than what we've already been doing, so what's the point? The magic lies in modelling multiple bounces. Remember, we reflected over the yellow wall to say we wanted our bounce to be off that wall, but we can chain these reflections to give multiple instructions to our bounces. If we first reflect over the yellow wall and then the magenta wall, we create a doubly mirrored world with our straight line showing the path of what 2 bounces looks like.

Reflecting over a second wall gives us another straight-line intersection to find our first and therefore second reflection point too.

If you want to convince yourself this trick works for multiple bounces, I recommend finding the congruent angles within the mirrored world's straight line and the actual bounces within the room in question.

An important part of finding this mirrored world's straight line though is the fact that it intersects the colored walls in the order the assassin's bullet bounces. In the initial setup provided, the straight line hits the yellow wall first before intersecting the magenta wall, just as the beam's bounce path reflects off the yellow then magenta walls in that order. If you move the assassin and target, you can see this idea holds for a magenta then yellow wall bounce too.

So, if we wanted to model the assassin's hitting the target in more bounces, we just reflect our room more times and draw the straight line between the assassin and mirrored target.

Even with many more reflections of the room, our bullet still bounces off the colored walls in the order our straight line intersects them. Try dragging both the assassin, target, and mirrored target to see how the paths change. Note these are only paths that result in the assassin successfully hitting the target.

Moreover, since squares can tile the plane maintain the same "silhouette" under reflection, we can infinitely tile the plane with reflected copies of our room. Since a line through this plane can represent any bounce shot from the assassin in the original room, we have successfully simplified our problem setup. Why? With straight lines, we can now use coordinate geometry to place our bodyguards and not worry about annoying reflectedl light patterns within our square.

In more math-y terms, we have turned our original room into what is known as a flat torus (yes, the thing that's equal to a coffee cup). Essentially, all this means is that our problem sort of exists in a world similar to the game of Asteroids: as you exit the top or left of one flat torus, you enter through the bottom or right of another one (and vice versa). This fact is what allows us to tile the plane consistently with our problem setup. If you look back at the 2-by-2 grid setup from before modelling the 2-bounce paths, you'll see that our top/bottom edges are both cyan and our left/right edges are both gray, showing that exact relationship we'd expect in a flat torus.

Connecting opposite edges of a square turns it into the equivalent of a torus.

This is the first key insight to solving this problem: turning our bouncing shots into straight lines in an infinitely tiled plane. Working with straight lines makes life so much easier than bent ones. With that, we can move on to the second epiphany to prove our result.

The (Different) Core 4

Even though we tile the plane infinitely, there aren't an infinite type of rooms. Just looking at our 2-by-2 grid that makes our flat torus shows us everything we need to know: there are exactly 4 types of rooms that build our tiling: the original one, the one reflected over the yellow wall, the one reflected over the magenta wall, and the one reflected over both walls. This regularity is clear visually: watch what happens if I reflect the target into every mirrored room.

Having 4 "unique" rooms generates 4 unique lattices of mirrored targets.

Each one of the reflected rooms generates a lattice of that reflected target! I've colored the 4 different lattices in green, yellow, magenta, and cyan. Now, since each dot represents a way of hitting our target, we just need to block every line from the assassin to any one of these colored dots.

This is the second critical idea to finish out this proof: every reflected target falls into 1 of 4 possible lattices (each represented by a color). Dividing the mirrored targets into lattices is nice since it places all dots in a given lattice to be the same distance away from each other.

At this point, you have everything you need to finish this proof using the flat torus tiling and the 4 lattices. If you want to try and finish it through, I recommend doing so as it has some pretty satisfying reasoning throughout it. If you just want to keep reading, I'd recommend visiting Bradley's post where she completes the proof there.

Once you reach the end of the proof, you'll find that you need exactly 4 bodyguards to protect any given lattice, and since there are 4 lattices, we need $4 \cdot 4 = 16$ bodyguards total to completely protect the target.

No matter where the assassin shoots, the target remains safe and sound. Try moving either of them around, and watch the bodyguards adapt and reduce the assassin's efforts to nil.

Since it is possible to protect the target from the assassin with a finite number of bodyguards, we can say that the square is a secure polygon.

What Next?

This is one of the most surprising facts I've come across in a long time. But, there's more places to take these billiard problems and dynamical systems. One of the first extensions I thought of upon seeing this was other grids. As we know, there are also hexagonal and triangular grids in addition to the square one we analyzed today.

Examples of triangular (left) and hexagonal (right). Are they secure polygons?

Not to mention, every other regular polygon doesn't tile the plane, so modelling their bouncing paths will be even more difficult. What about non-regular polygons? Or concave ones? This is definitely something I'll revisit in the future and try to find the conditions for a polygon to be secure, but until then, we have just scraped the surface of billiard problems and dynamical systems.

A few other, related problems to consider. While we only looked at rays for light sources, others have considered other types of light sources. In an Illumination Problem, we consider point sources (i.e. light source that produces light in every direction instead of one). Actually, we've already looked at one type of Illumination Problem: the secure square! It can be rephrased as the the following: if a light bulb is placed in a mirror room, is it possible to place a finite number of pillars such that a given spot is never illuminated? It's idential to our secure polygon question. One of my favorite Illumination Problems is the Art Gallery Problem, which is not only a readily applicable problem, but also has a wonderfully elegant proof that Steve Fisk conjured (it speaks volumes how nice this proof is for it to be in Martin Aigner's Proofs from THE BOOK). Here's a great, in-depth paper I found discussing this famous problem along with some proofs and extensions as well.

Even outside of classic billiard problems, even just knowing of the simple reflection technique to model bounces is invaluable. Grant Sanderson of 3blue1brown fame used bouncing light as an analogy to solve a kinematics problem and bring in circles almost magically. I've said it before, and I'll say it again: duality and different perspectives are some of the most powerful problem solving tools you can have. This small reflection technique, or the complex number algebra with Alhazen's problem, might not mean much to you now, but it's another tool to stow away in your back pocket. Despite only seeing this ability to turn dynamics into geometry, I've seen them enough to know that these techniques and ideas are more than just an intriguing fact. You'll never know when you might be able to use such a tool, but when you do, who knows the new worlds that a new paradigm can unlock for you.

If you're interested in learning a bit behind today's graphics and widgets, see the follow up I wrote up detailing some seemingly innocuous math with some high-budget applications and cool patterns.