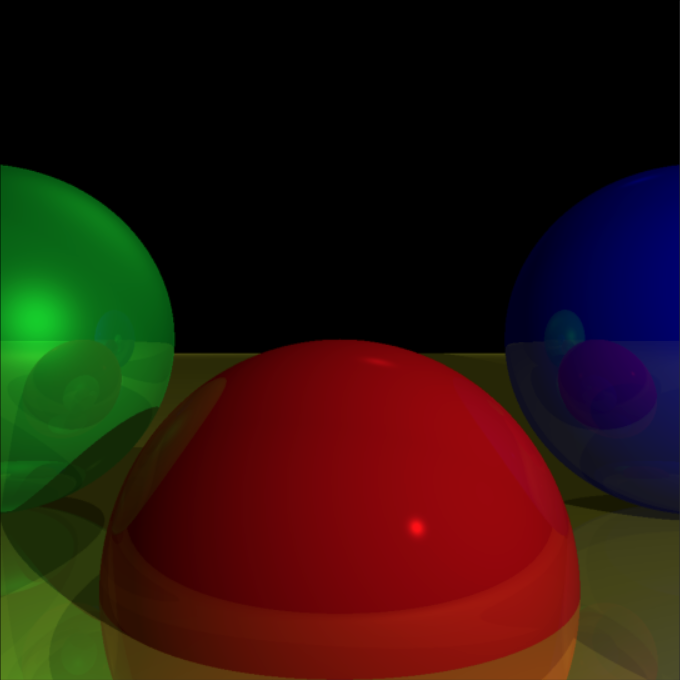

A couple months back, we covered a little bit about some random circle computations and facts I had collected over the months leading into that post. In it, we highlighted and rederived the basic raytracing equation for circles and spheres. In a few words, we used properties of vectors to be able to reduce the problem of where a line intersects a sphere into a quadratic equation. And with all quadratics, we were then able to use the quadratic formula to quickly find those points of intersection. In that post, I go on to say that I was able to generate this incredible raytraced scene in a mere matter of tens of minutes in even as simple a programming language as Python:

This raytraced scene is just millions of uses of the quadratic formula.

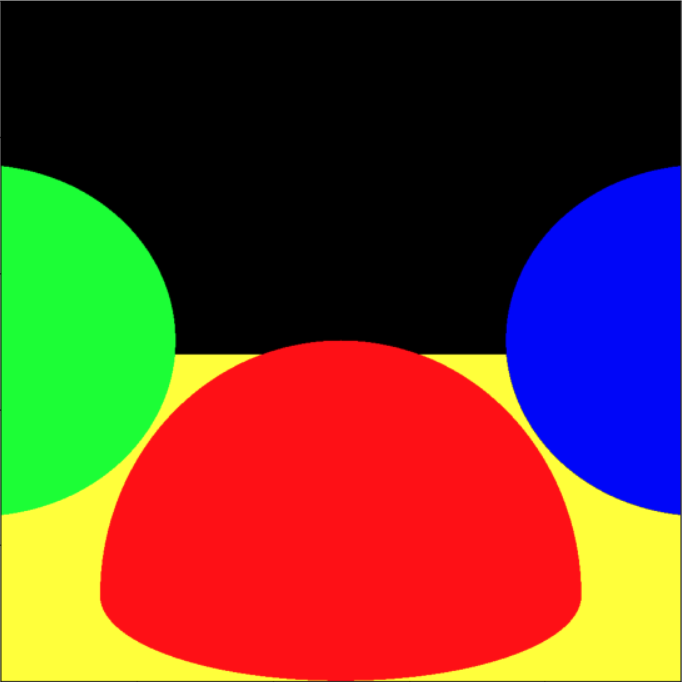

But I have to admit, I sort of lied to you. While, yes, that image does use the quadratic formula millions of times, it doesn't only do that. To render shadows and reflections, the scene also had to compute lighting and the physics you'd expect with mirror-like objects. Without any of this, our scene would just look like, well, uh, this:

Now this is a peak graphical performance. In a word: art.

Whichever one you think is better looking is up to the eye of the beholder, but what can't be argued, is that the second image is much cheaper to render; I'm sure you could guess, no shadows and reflections causes the scene to be rendered in a fifth of the time. A fifth.

Quizzing Quotients

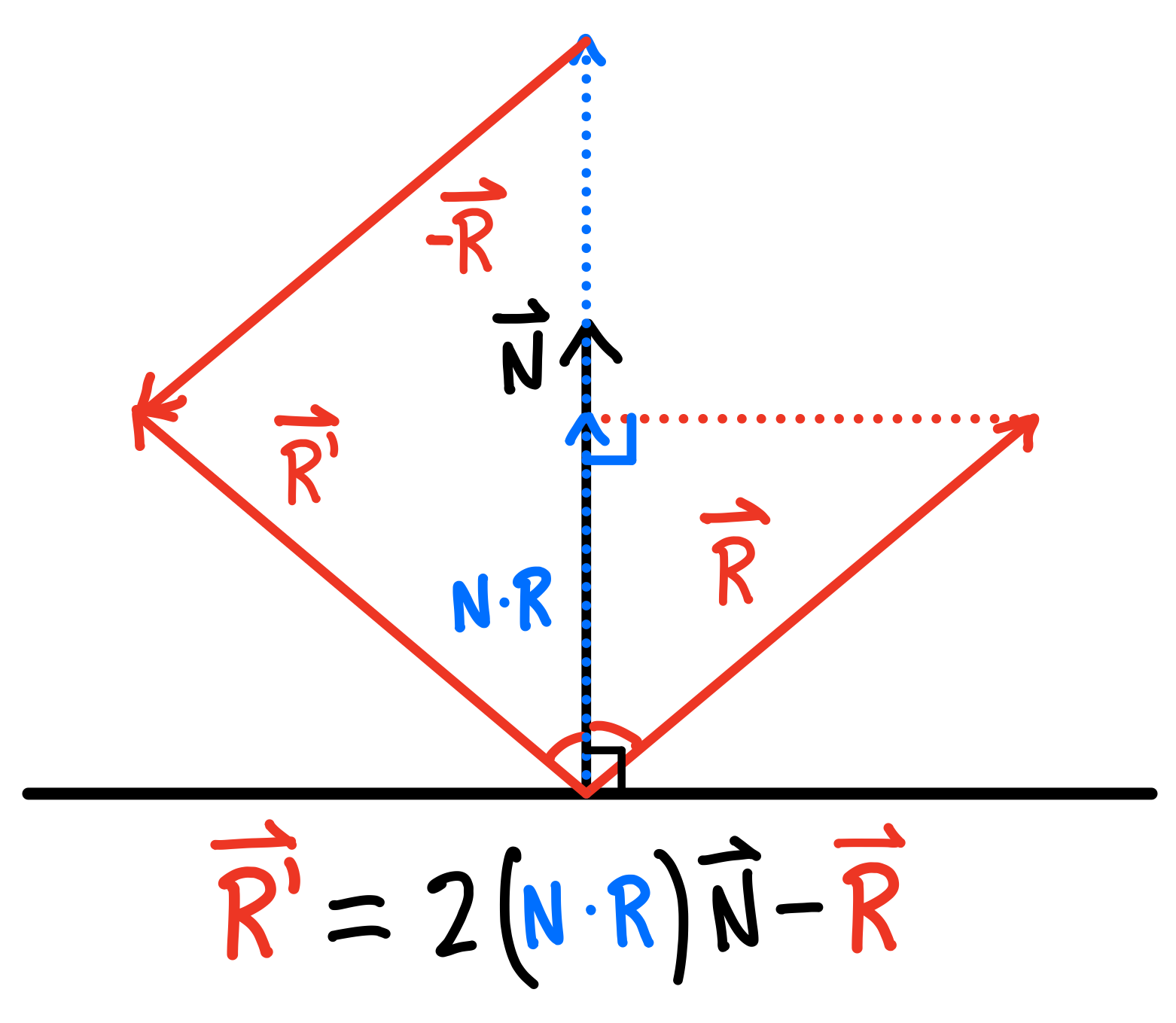

Intuitively, more stuff to compute should take a computer a longer amount of time to go through, but can we pinpoint this bottleneck? Let's quickly look at what it takes to compute some of these reflections. When light bounces off, say, a mirror, these calculations become much easier when we use the mirror or surface's normal vector: the vector perpendicular to the surface (or the point at the surface) in question.

How to reflect a ray over a normal vector.

The above formula for reflecting a ray works in general for reflecting any ray $\vec{R}$ over another vector $\vec{N}$ (even if they're not normal)… Under a small assumption: the vector $\vec{N}$ is normalized (yes, the naming scheme isn't ideal), or of unit length (denoted by a little hat $\hat{N}$). We can do this by just scaling the vector down by its own length:

Recalling that the length of a vector 3D $\lVert N \rVert = \lVert <x,y,z> \rVert = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2}$, we end up with

And here lies our bottleneck. While we, as humans, treat division not too differently from multiplication in theory, computers can't work with "just in theory"; computers have to actually compute this arithmetic somehow. It turns out, while multiplication is a bit more complicated than addition, we've been able to make algorithms for decades to accelerate the computation. Division, on the other hand, has been such a difficult endeavor to match other operations speed, major companies like Intel have lots of research dedicated to this alone.

So, what do we do?

The Fast Inverse Square Root

Under pressure, people can do some amazing things. You can imagine if someone was making a game or anything that required lots of lighting calculations, say, in a video game, calculating $\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}$ millions of times, therefore also computing millions of divisions won't really cut it.

The developers of the video game Quaker III, an incredibly fast-paced shooter that definitely needed these optimizations, used a now infamous algorithm aptly called the fast inverse square root, because, well, it computes the inverse square root $\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}$, fast and avoids dreaded division. The history of the algorithm has been found to predate the game that made it so infamous, but pop culture assigns value to whatever it latches onto first. Without further ado, the original source code (along with all the original comments and annotations) for Quake III was released in 2005, and the program is right there for us to learn from:

float Q_rsqrt( float number ) { long i; float x2, y; const float threehalfs = 1.5F; x2 = number * 0.5F; y = number; i = * ( long * ) &y; // evil floating point bit level hacking i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 ); // what the fuck? y = * ( float * ) &i; y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 1st iteration // y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 2nd iteration, this can be removed return y; }

It's not a long algorithm by any means, but I think the comments themselves explain just how crazy this is; even the developers who USED it are impressed, but let's break it down line by line.

long i; float x2, y; const float threehalfs = 1.5F;

Here we define four different numbers: i, x2, y, and threehalfs. But not all of these numbers are treated the same.

Binary and Floating Point

In our day-to-day routine, we (at least, most of us) use base 10, decimal, to represent our numbers. What this means is that each digit in a number corresponds to some power of 10 we add together. For example, the number 1409, can be grouped as

with 1 thousands, 4 hundred, 0 tens, and 9 ones. You add these all together to get $1(10^3) + 4(10^2) + 0(10^1) + 9(10^0) = 1409$. This may seem obvious, but this is a really important idea in how we write numbers. Each digit represents a condensed shorthand for how many of a specific power of 10 is in our number. Computers do it similarly, but instead of base 10, they use base 2, or binary. If we wanted to represent 1409 in binary, we'd have

Now if you went and added these together you could verify that $2^{10} + 2^{8} + 2^{7} + 2^{0} = 1409$. Now each digit—or decimal-igit—represents a power of 2. We call these binary-igits bits. That first line of code that defines a long i means we define a number with 32 bits that looks like

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000

With 32 bits, we can write any number from 0 to $2^{32} - 1 = 4294967295$. Let's notice some nice properties with this format. In decimal, if we wanted to add a 0 to the end of our number like $1409 \rightarrow 14090$, this is the same as multiplying our number by 10, because now every digit has moved up into one bucket higher than before.

In the same way, we can remove zeroes on the right $14090 \rightarrow 1409$ by dividing by 10 since every digit will be shifted into one power lower. Binary works the same. If we want to add a 0 to the right end of our number, we now multiply our number by 2, but if we wanted to remove a 0, we divide by 2. This is known as bit shifting, and serves as one of the nice workarounds of division: if you want to divide specifically by a power of 2, just bit shift the number in binary by however many zeroes you need.

But that leads to an issue: only even numbers can be wholly divided by 2, so what do we do if we want to divide an odd number? How would we write a decimal like .5? How would we write any rational number? We currently can only represent 32-bit integers, since we have no way of writing fractional parts. If we wanted to add decimals, why don't we just throw in a decimal point then?

00000000 00000000 . 00000000 00000000

(Remember this decimal point is just for our convenience; the computer doesn't actually see anything here but the 32 bits) If we use the left 16 bits for the integer part, and the right 16 bits for the decimal, we can now in fact write rational numbers, but all of a sudden the range of numbers we can represent has shrunk immensely, only to just under 65535.9999847, but the upside is now we can do much more precise, rational numbers. This is okay, but we can do better.

If you have ever taken a chemistry or physics class, you're probably all too familiar with scientific notation. We can write really big numbers and really small numbers in a much more condensed way by turning everything into a product of a power of ten:

This is how our calculators can do arithmetic beyond just the digits shown on the screen. By slapping on a power of 10, we can now represent a much wider range of values using the same number of digits previously. Similarly, binary works just the same except with powers of 2.

So, let's do just that. Let's allocate 8 bits of our previous 32 to representing the exponent, and another 23 to our actual number.

00000000 0.0000000000000000000000

With 8 bits for the exponent, we can represent anything from 0 to 255, but we also want negative exponents, so we just subtract 127 to get the new range of exponents from -127 to 128. With our fractional number and its 1 whole bit and 22 decimal bits, we can represent numbers from 0 to 1.999999761581. We call this part of the number the mantissa. However, this is actually not the full extent of the potential precision we can get. In all of our examples of scientific notation, there was always a non-zero number before the decimal point, since if there was a leading 0, that's another power of our exponent we could factor out. In binary, there's only two values: 0 and 1. If we know the first digit is non-zero, then we know it has to be a 1! So we can actually shift our decimal point over and gain an extra bit.

00000000 .00000000000000000000000

Now all we have to do is affix a leading 1 and we're good to go. So, the number

11001010 .01110100000000000000000

would represent $1\color{blue}{.453125} \cdot \color{green}{2^{202-127}}$. In general, if we're given a 23 bit number representing the mantissa and an 8 bit number representing the exponent, we can write our number we're expressing as:

We divide our mantissa by $2^{23}$ so that it is only the fractional part of our number like we want. However, doesn't part of this just feel wrong? Like, when we were defining an integer as a 32 bit long, we used every bit to denote a new power of 2. Here, we really are writing two different binary numbers side-by-side. If we wrote our number as

.01110100000000000000000 11001010

would it really make a difference? So, just for the sake of consistency, we'll put the exponent first, and we can then represent our number's bit representation as a sum:

We just added 23 filler zeroes to our exponent to make sure it landed where we wanted to in the final bit representation. That sounds like a bit shift! We can thus multiply our exponent by $2^{23}$ to give us our 23 extra zeroes So, this final sum—our exponent and mantissa together—can be written as

Now, there are some flaws that do need to be addressed. If we assume our leading bit is non-zero, how _do_ we represent 0? That actually doesn't matter in the grand scheme of our intended use in lighting (i.e. we only call the fast inverse square root when we have to use it), and when we're not, this is a single edge case that can be put in later. Yeah, I'll admit, it's not ideal, but it gives us more precision where we need it. The other issue is we haven't used all of our 32 bits! $8+23=31$, so where did our last bit go? In our set-up, we have it such that we can only represent positive numbers. We can attach an additional sign bit at the front, where if it's a 0, we say the number is positive, and if it's a 1, the number is negative.

0 11001010 .01110100000000000000000

However, we want to know how to find positive square roots, not enter the complex world, so we always just assume it's positive. So if we don't use the bit, why don't we repurpose it? Conventions. The standard for binary fractional-part representation and arithmetic is known as IEEE 754, and for that reason we just have to abide by it.

I've been calling this with terms like "decimal points" and "fractional-parts", but a decimal point seems wrong when we're doing it in binary. The type of number we've just formatted is called a floating point or a float as we see in lines 2 and 3. While floats give us nice ways to represent a lot of numbers, they are a bit annoying compared to longs in the sense that we can't bit shift or manipulate a float since the bits in a float represent multiple, different parts of the number in question, namely the exponent and the mantissa.

Bit Approximations… With Themselves?

This may seem like a gross, unnecessary dive into how computers understand numbers, but understanding what binary, bits, and floats are will help us greatly in understanding the ingenuity behind the fast inverse square root. To recap, we've found that we can represent a binary number as a float with two parts, an exponent and a mantissa, as if we were using scientific notation. To find the actual number our float represents, we use the formula

Since we're working with two different binary numbers together, we combine them into one sequence of bits that to as a shorthand to represent our float with the formula

We can now perform some mathematical magic. Let's take the logarithm of the actual number of our float (note by $\log(x)$, we assume it to be $\log_2(x)$ since we're working in binary).

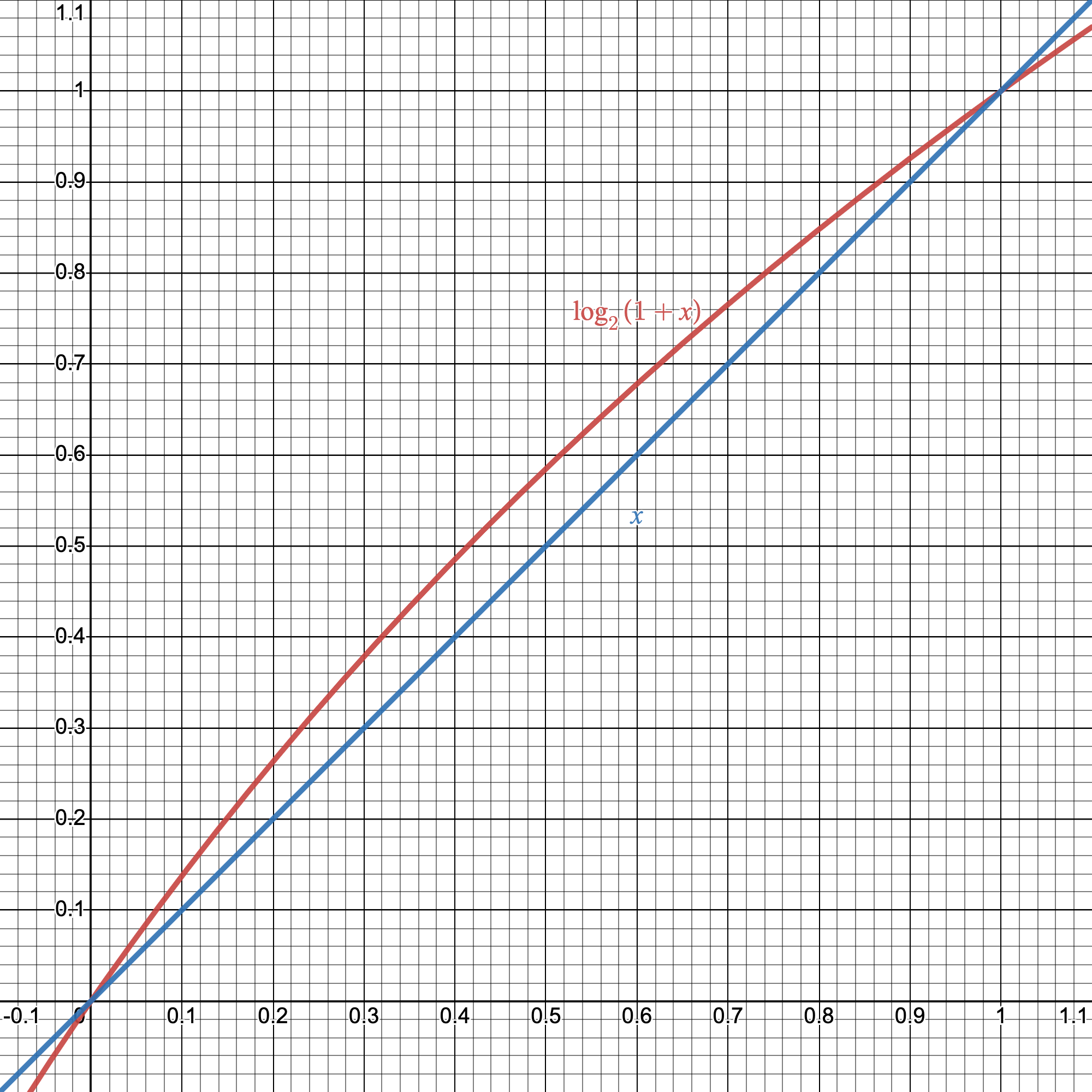

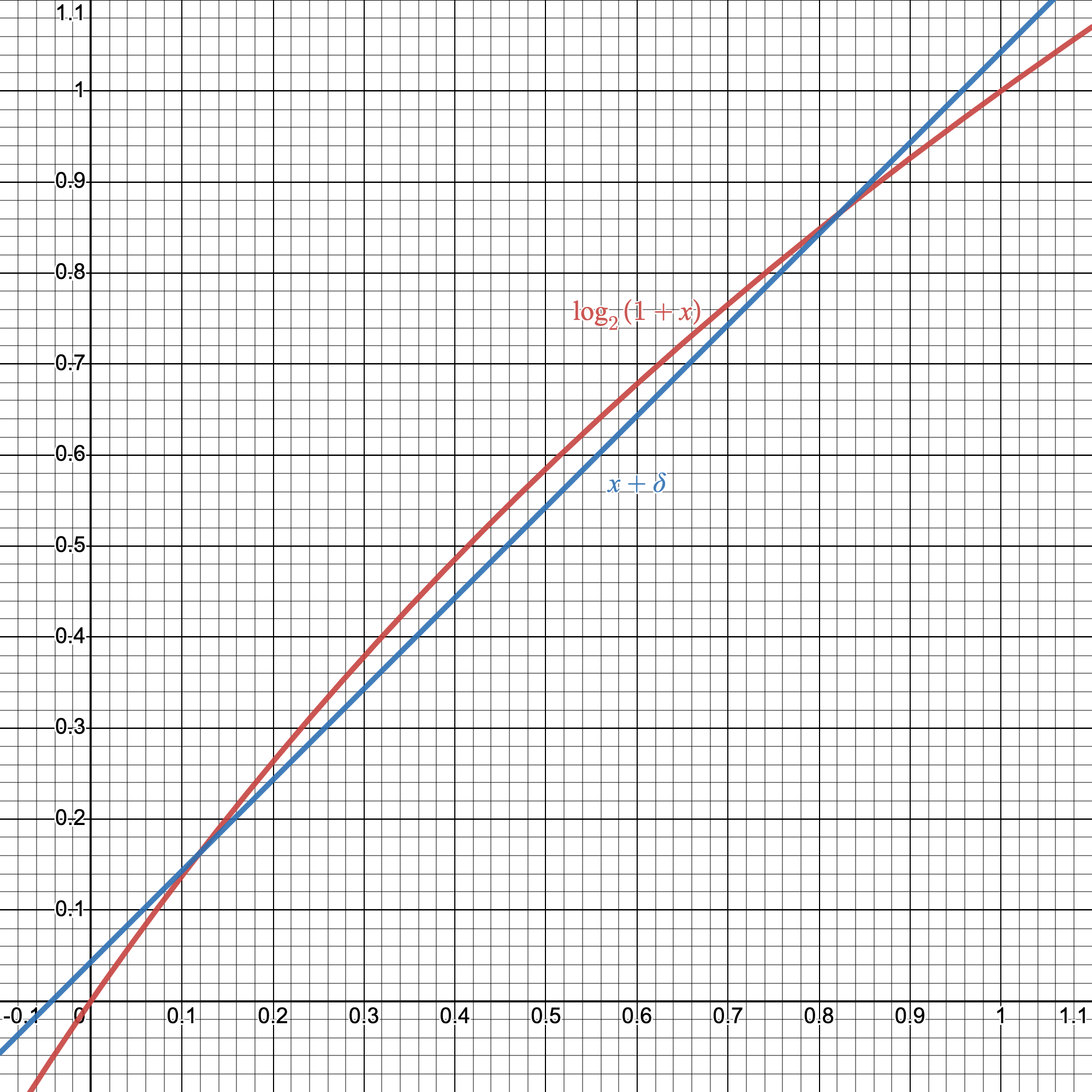

This may not seem that useful, but there's an important detail here: we're looking to optimize a program, not get exact results. So, a useful fact to note is that for $x$ between 0 and 1, $\log_2(1+x)\approx x$.

We can simplify $\log_2(1+x)$ by approximating it as $x$.

We can get an even better approximation by slightly offseting our estimate; $\log_2(1+x)\approx x + \delta$ is a better approximation than $\log_2(1+x)\approx x$

We can approximate $\log_2(1+x)$ better with small shift.

It turns out the best value for $\delta = 0.0430357$ (as in minimizing the average error). By definition, our mantissa is between 0 and 1, so we can use this approximation ourselves.

If we rearrange this a bit,

Okay, why did we do any of this? This definitely is kinda random to not only take the $\log$ of our float, but also do all these approximations to then get rid of that $\log$ too? Why?

Look inside the parantheses in the above equation.

That's precisely the bit representation of our float! So, in a way, the $\log$ of our number is equal to the bit representation of our float, up to some scaling and shifting.

With this under our belt, we can finally start looking at the steps of the fast inverse square root algorithm.

Evil Floating Point Bit Level Hacking

First, we assign our number we want to find the inverse square root of into a float (a.k.a. scientific notation-type decimal number).

y = number;

Now, recall that a float isn't that compatible with bit shifting or that many operations, so here's the first clever part of the algorithm.

i = * ( long * ) &y;

What this does is we take the exact bits of our number as a float and copies it into a long. That's it. Under the hood, it takes the number at the memory address of y and exactly transfers the bits over to i. This will make our life easier here in the next step.

Since we have now put our number that we're trying to find the inverse square root to, y, as its bit representation, we have effectively stored approximately $\log({y})$ into i.

What the F#@k?

The fabled step that makes this algorithm so smart.

i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 );

Remember, at the end of all of this, we want to find a number, $\alpha = \frac{1}{\sqrt{{y}}}$, but we have been working almost exclusively in logarithms. So, let's take the $\log$ of both sides.

Wait, but we have a division in there! On quite the contrary, it's a division by 2, and since i is a long, we can just bit shift to the right 1 to divide by 2! That's precisely what i >> 1 does: it bit shifts i once to the right.

But what is the deal with that 0x5f3759df? Well, remember that i is only an approximation for the $\log(y)$ up to some constants. So, we have to account for those constants somehow. Let's go back to $\alpha$. We know that

In terms of floats…

Fortunately we already know how to expand this from before.

This looks pretty bad, but after some simplifying and rearranging…

We know that anything of the form $E\cdot 2^{23} + M$ is just the bit representation of the number, and we know the bits of $y$ is just i, so

That magic constant 0x5f3759df is the hexadecimal (not totally sure why there is so many changes of bases) approximation of that constant $\frac{3}{2}2^{23}(127 - \delta)$. So what we do in this line of code is we bit shift i once to the right to halve it, and take that result and subtract it from 0x5f3759df to correct for all the constants that came with our approximations of $\log(y)$. Not totally sure why the developers felt the need to write a variable for threehalfs and not this number, but what can we do.

But now note we are storing this value in i. So, from here on i no longer refers to the bits of $y$, but the bits of $\alpha$, our desired number. The bits, though, aren't particularly helpful since we want the float and decimal representation of $\alpha$, so we do just that:

y = * ( float * ) &i;

Just like how we casted the bits of a float $y$ into a long i, we now do the reverse and cast the bits of i into a float $y$.

At this point, we're technically done: $y$ currently stores an approximation of $\frac{1}{\sqrt{\texttt{number}}}$, using 0 steps of slow division! But we can do better for a marginal amount of extra computation.

1st Iteration

Say we wanted to solve for the zeroes of the function

where $C$ is any arbitrary constant. Solving for $y$…

If we could find a way to approximate the roots of this function, we'd then in turn have a way to approximate the inverse square root of any number!

In a previous post, we discussed a technique to precisely do that: the Newton-Raphson Method (sometimes just called Newton's Method).

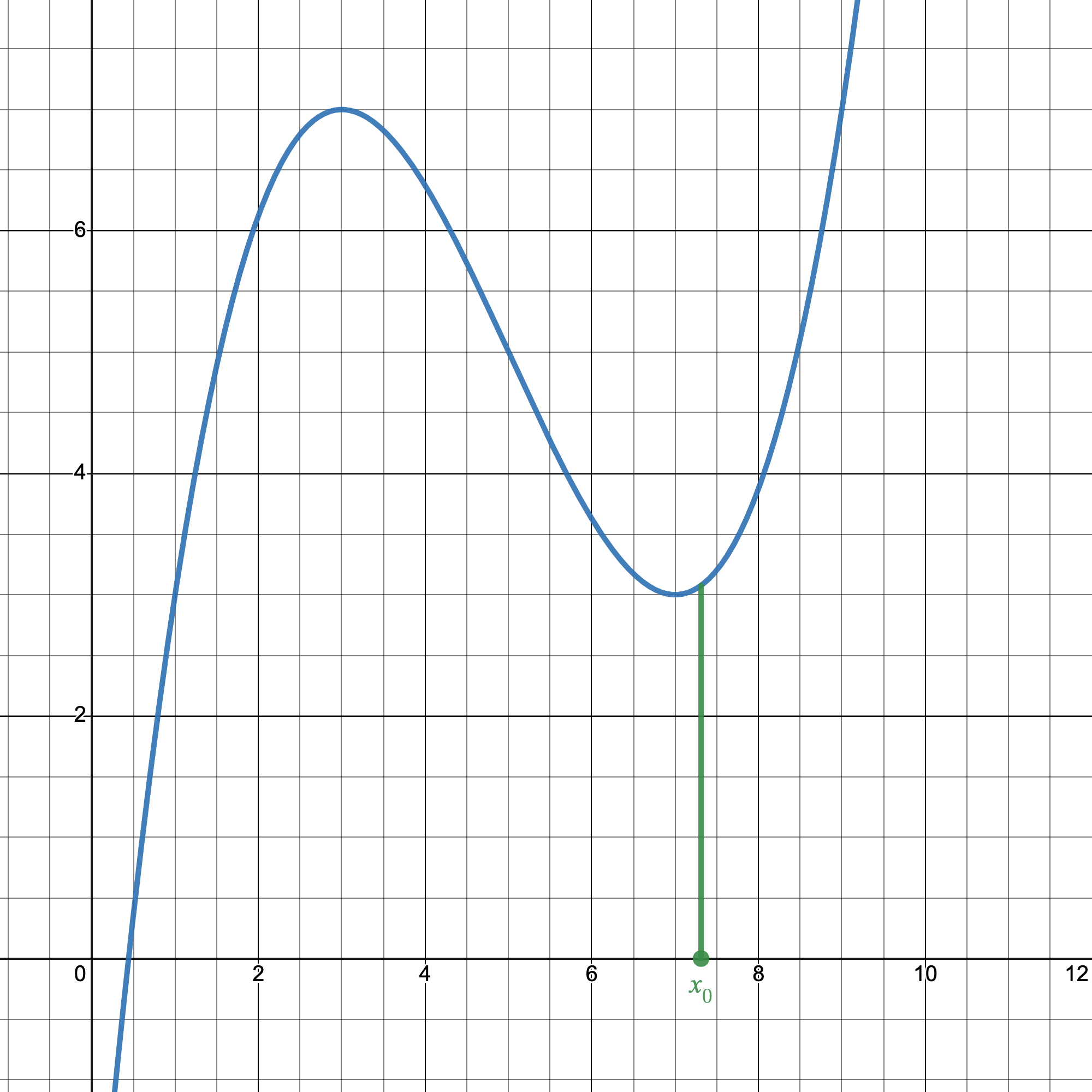

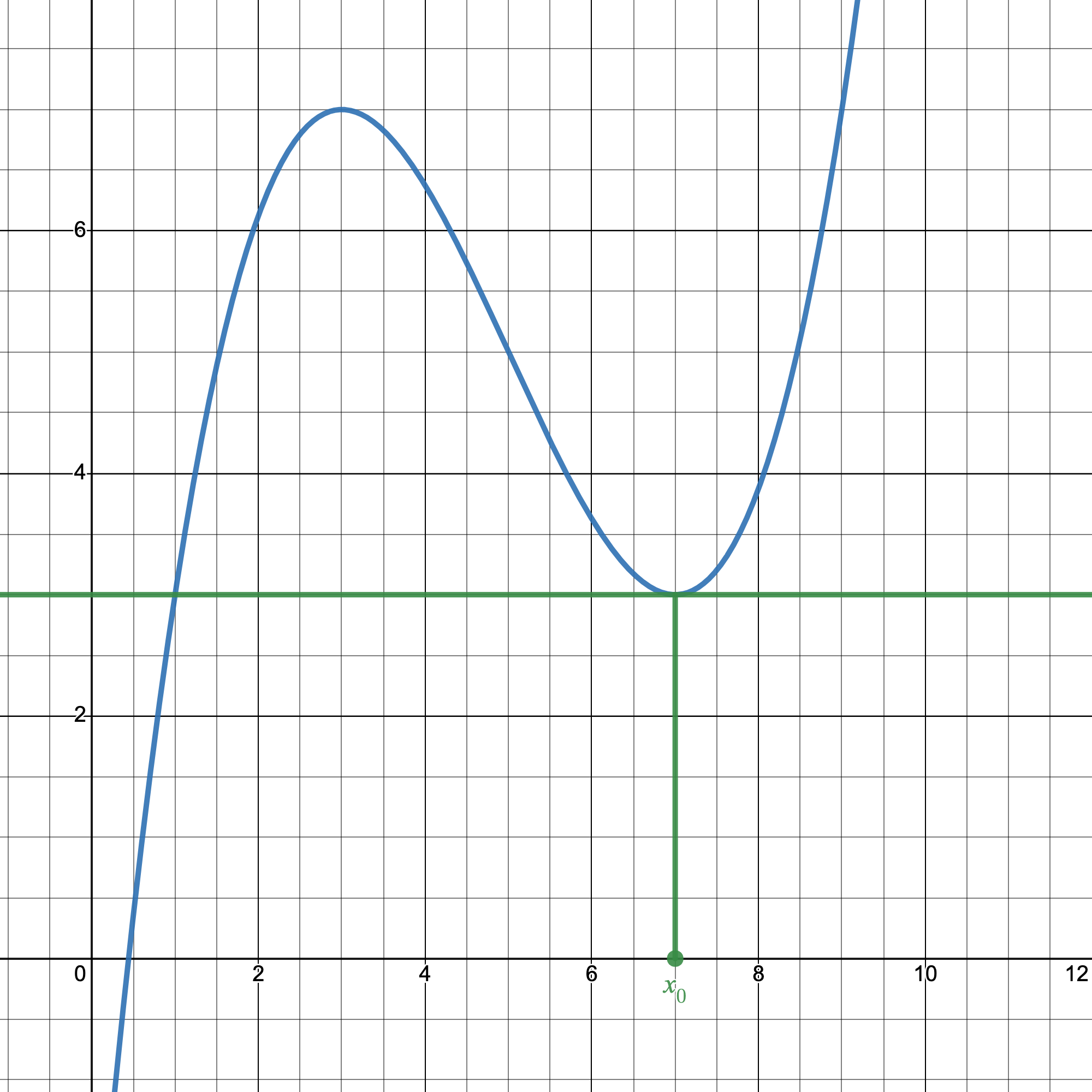

Let's say we have a random function $g(x)$. To find a solution, what can we do? Well, not a good idea, but an idea, we could just guess a random number $x_0$ as a solution. If $x_0$ is a solution, then obviously $g(x_0)=0$.

A pretty bad first guess.

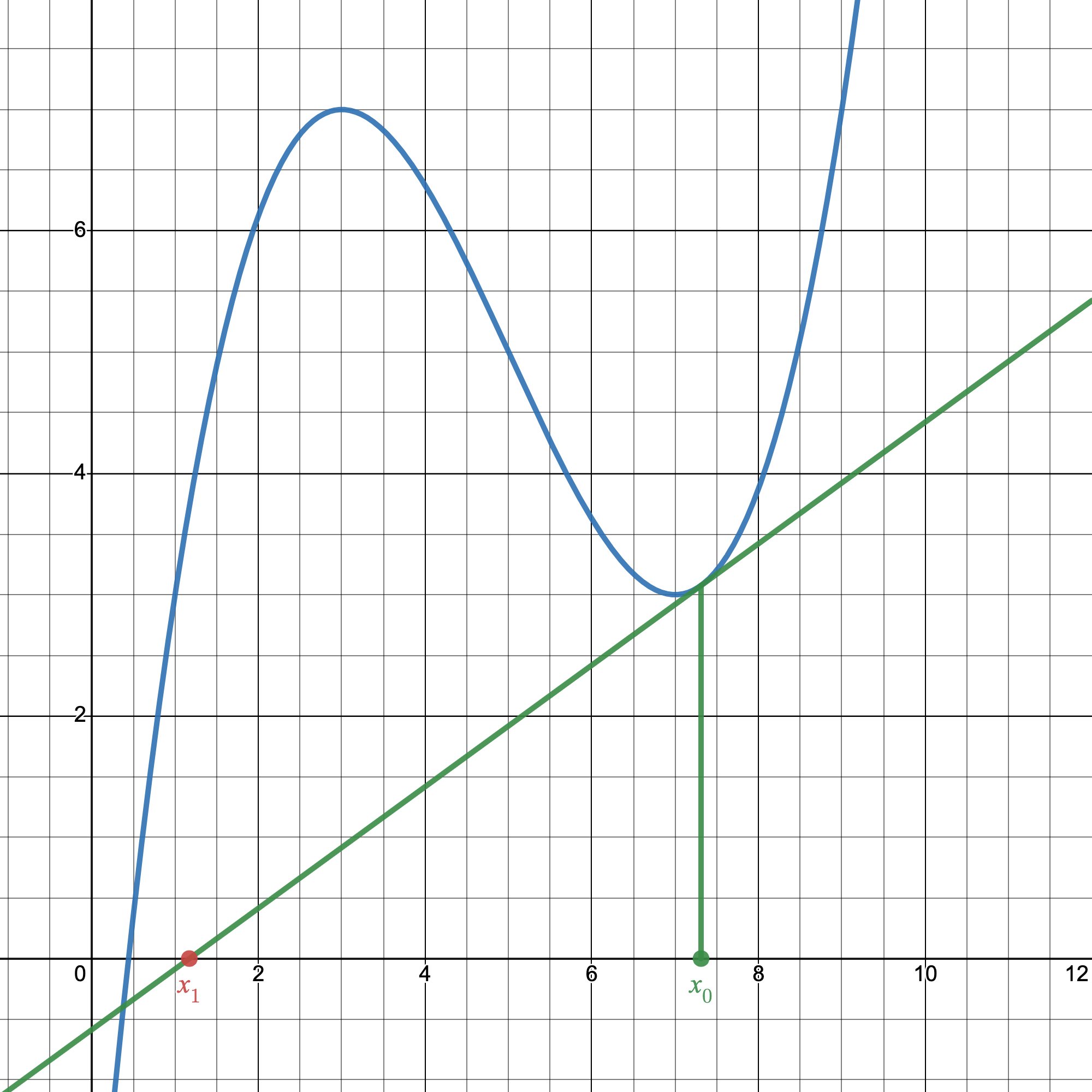

As you'd imagine, the chances of guessing a root of $g(x)$ immediately is slim. So, the next step in Newton's Method tells us to draw the tangent line at our first guess $(x_0, g(x_0))$ to get our next guess $x_1$.

A better, but still not ideal, approximation.

Now we're getting pretty close. That's the whole premise of the Newton-Raphson Method:

- Pick an initial guess $x_n$

- Draw the tangent line at $(x_n, g(x_n))$ and find where it intersects the $x$-axis

- Use that as your new guess $x_{n+1}$

- Repeat steps 1–3 as needed

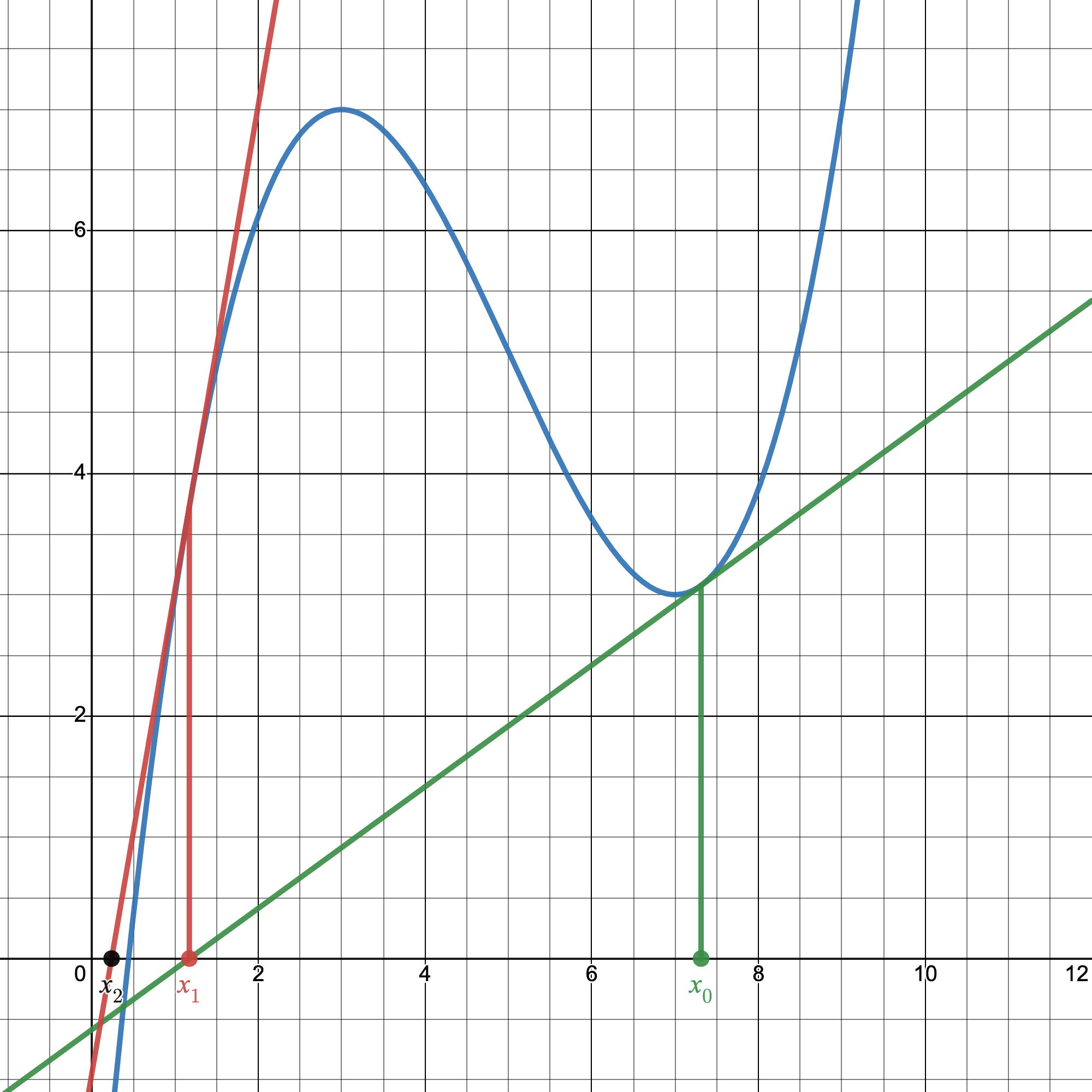

So, if we do another iteration of our example above…

Now we're getting to a reasonable estimation.

There are some edge cases though where this obviously won't work, such as if our guess happens to hit an extremum.

In this case, there's no additional guess since our tangent line is parallel to the axis.

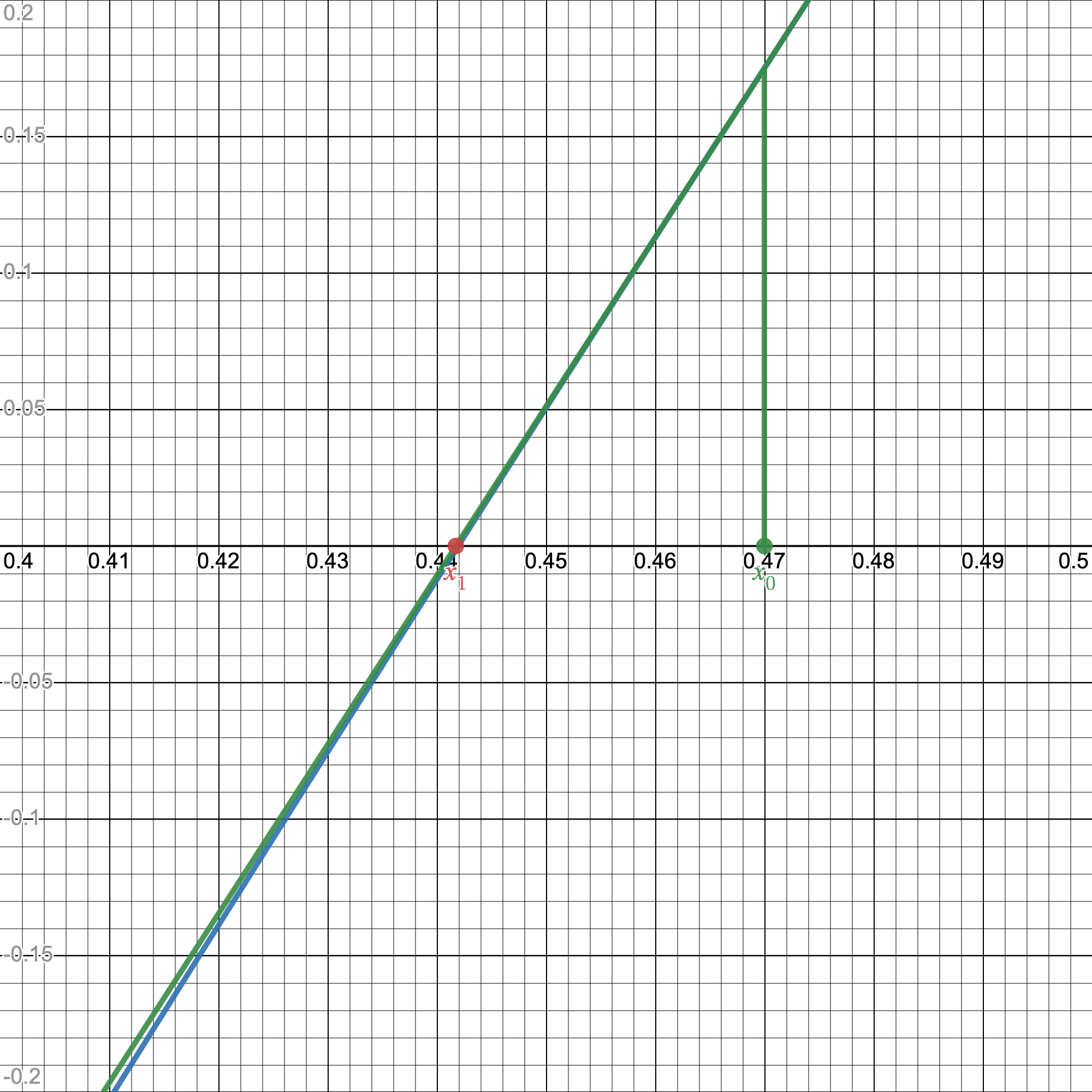

We could even get loops where we just continuously bounce back and forth between two guesses. Fortunately, we don't have to worry about that. If our first guess is already really accurate and near the actual solution, then our graph $g(x)$ begins to look like this:

Up close, smooth, continuous graphs look linear.

$g(x)$ starts to look like a line! And when a function locally looks like a line, it also locally looks like its tangent line.

Can't really beat that now.

This is important to us since we already have a good estimate from all of our bit manipulation from earlier, so we do one iteration of Newton's method to get an even better approximation.

To put this in terms of some equations to compute, we want to estimate the root of

Given an initial guess $y_n$, our next guess $y_{n+1}$ is the solution to

since this describes where our tangent line generates our next solution. Solving for $y$ we get that

Now it's just a matter of plugging everything in.

With a small substitution of $x_2 = \frac{C}{2}$,

If we look at the line of code that entails this "1st iteration",

y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) );

That's precisely the formula they have right there. You might wonder if that $\frac{3}{2}$ poses an issue at all in terms of division, but it is of no concern since we know its decimal expansion to be 1.5 so we can just use floating point arithmetic from the start; division becomes an increasingly hard problem when we don't know what the decimal representation of the quotient in question is.

Conclusion

Let's quickly recap what we've learned about the fast inverse square root algorithm and how it works:

float Q_rsqrt( float number ) { long i; float x2, y; const float threehalfs = 1.5F; x2 = number * 0.5F; y = number; i = * ( long * ) &y; // evil floating point bit level hacking i = 0x5f3759df - ( i >> 1 ); // what the fuck? y = * ( float * ) &i; y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 1st iteration // y = y * ( threehalfs - ( x2 * y * y ) ); // 2nd iteration, this can be removed return y; }

- We first take our number as a

float$y$ and store its bits in along i. - Noting that $\log_2(y) \approx \texttt{i}$, we approximate $\frac{1}{\sqrt{y}}$ using bit shifting and the magic number 0x5f3759df.

- We then perform one iteration of Newton's method to get an even better approximation.

These three steps required a fair bit of knowledge to properly unpack, but it's incredibly insightful when thinking about the lenghts programmers go to optimize their code. Remember: this is all to avoid using any division! What we consider such a simple operation is almost never such for a computer, and when it comes to teaching computers to do these things, they are as blind as a bat. But it's this difficulty and blank slate of a circuit board that makes computers be able to teach us, just as much as we teach them.