If you ever seen a bike at night, you've likely noticed the bright reflector many people use to ensure they're visible while riding. Why are they so effective at creating such visibility? It lies in the construction of the reflector itself. Looking closely at a bicycle reflector, you will notice that they aren't just plain mirrored facets; they have an almost pixelated, grid like look to them.

They are surfaces not covered in flat mirrors, but rather are tessellated with the corners of cubes that are mirrored. Why is that? To find out, we first need to talk about Fermat's principle, and $90^\circ$ angles.

Fermat's Principle

Fermat's principle, or the principle of least time, was an idea coined in 1662 by the mathematician of the same name, and it states that the path taken by any given ray of light is always the quickest one. Although this may seem obvious, it allows for many properties of light and optics to be derived from it. The one that it helps demonstrate for us is the common equality of the Law of Reflection: the angle a light approaches a surface is the same angle it reflects at.

Let's say we have a light source $S$, and we're reflecting it off a mirror (black) at point $R$, to have our ray reach an end point $E$. To show that the angle of incidence must equal the angle of reflection, we are going to create a mirrored copy of our end point, $E'$ (points $P$ and $Q$ are exclusively reference points). As $E'$ is a reflection of $E$ across the mirror, they are both equidistant to $R$, so we end up with two orange lines of equal length, $\overline{RE}$ and $\overline{RE'}$. However, because $\overline{RE} = \overline{RE'}$, our original path of reflection $SRE$ can be modeled with the new path $SRE'$. Note that the speed of the light isn't changing throughout our model, so we only need to find the shortest path $SE'$. To minimize $\overline{SE'}$, the shortest path is clearly just a straight line (blue). We already new that the angle $\angle{ERQ} = \angle{E'RQ}$ by definition of reflection of $E \rightarrow E'$, and now that we know $\overline{SE'}$ is a straight line, the angle that $\angle{SRP} = \angle{E'RQ}$. Combining these two inequalities nets us $\angle{SRP} = \angle{E'RQ} = \angle{ERQ}$, which was what we wanted to show.

Although this seems like an obvious fact, knowing why it this fact is true helps to understand how we will apply it to our bike reflector and corner cubes.

Right Angles

To understand why corner cubes are chosen as bike reflectors structure, looking at simpler cases always helps. Instead of looking at corners of cubes to see how light interacts with them, we can first work from the corner of a square and see what happens.

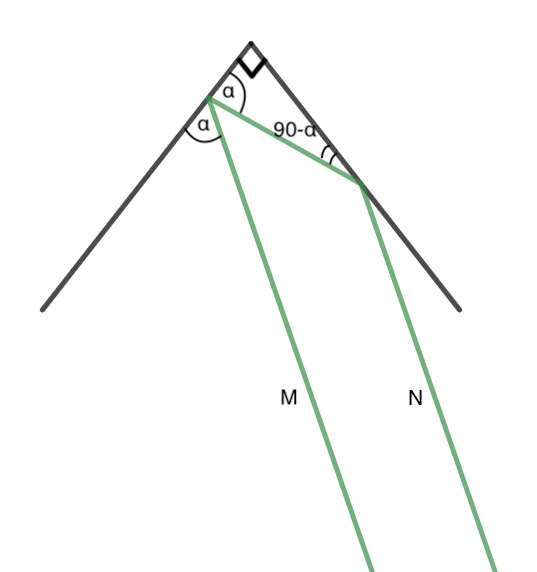

Notice how regardless of what angle the light is hitting the corner, the light reflected from the corner is always parallel to the ray entering it. We can prove this remains true for any angle $\alpha$ quite simply using some basic geometry.

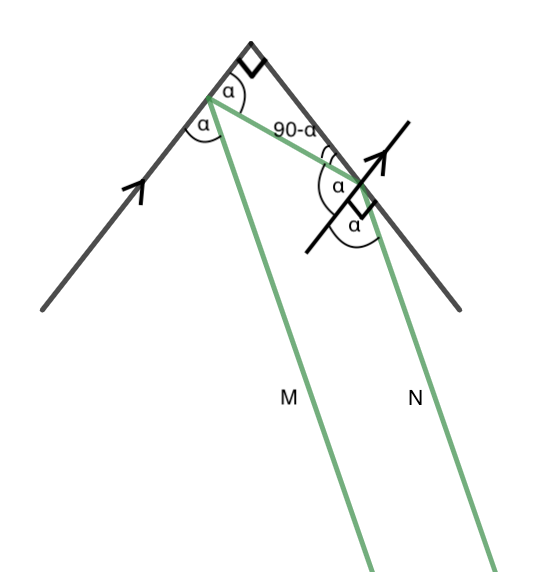

We want to show that ray $\overrightarrow{M}$ is parallel to $\overrightarrow{N}$ given $\overrightarrow{M}$ intersects the corner at an angle $\alpha$ and that we have a true square corner that is a right angle. Filling in the givens, the rest follows nicely. The Law of Reflection gives the angle congruent to the initial $\alpha$, and the idea that all triangles' angles sum to $180^\circ$ gives the $90-\alpha$. The trick in proving this involves adding an auxiliary line as such and the rest follows.

We add another line parallel to one of the sides of our corner. This creates another right angle. Since we know that $90-\alpha$ makes part of the right angle, we know that $\alpha$ must make up the rest of the right angle, as $90-\alpha+\alpha=90$. By Law of Reflection we then know that there is a symmetrical angle of measure $\alpha$. Now since $\overrightarrow{M}$ and $\overrightarrow{N}$ both are attached to parallel lines at congruent angles, the only way that can happen is if $\overrightarrow{M}$ was parallel to $\overrightarrow{N}$ as well. Hence, a ray $\overrightarrow{M}$ has a reflected path $\overrightarrow{N}$ that exits parallel to its ray of incidence.

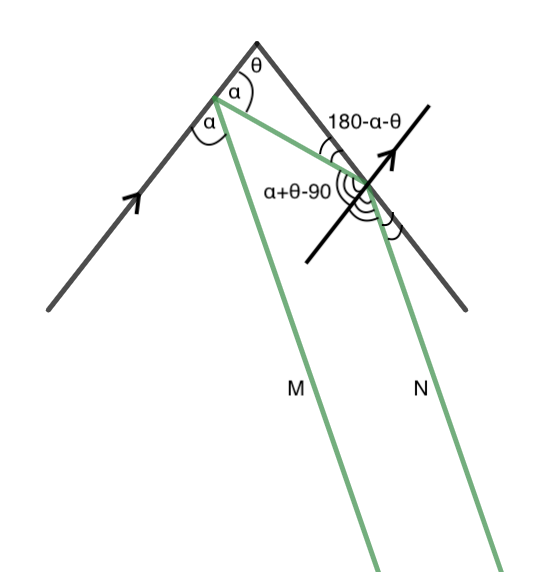

Moreover, we can show this only holds true for right angles using very similar logic. Setting our once right angle to $\theta$...

From our diagram, it's clear that for $\overrightarrow{M}$ to be parallel to $\overrightarrow{N}$, $\alpha=\alpha+\theta-90$, which when solving for $\theta$ gives $\theta=90$, our previous right angle.

All of the previous arguments can be applied to the 3-dimensional case by decomposing the ray of light into two other rays, and by showing that those two rays are parallel to the initial, that the composite ray is as well. With all of this together, it makes perfect sense why bike reflectors are corners of cubes: they send light back to its source. If you had a standard mirror, no light would return back to where it came from unless looking perfectly perpendicular to the mirror.

If no light goes back to its source, to say, a car's headlights, no light will hit the driver's eye to indicate that there is a bright, shining reflector to show that there is a bike up ahead (for this reason exactly, most reflectors actually have angles slightly large than 90$^\circ$ so that most light returns back to its source, and some can scatter to an observer slightly above/below/left/right of the source). These reflectors actually have a specific name to it, and they're known as retroreflectors, literally meaning to reflect backwards. This concept has been leveraged to aid satellites, and indirectly the military. There's a reason why no stealth-based aerial technology has no right angles: they want to avoid creating an accidental retroreflector that can return radio waves.

Hopefully this gave insight into a seemingly arbitrary design choice in one of the most common bike accessories used today.