This post looks to describe an interesting property intrinsic to any and all quartic functions, and it has to do with the relationship between the functions' inflection points. Below is a Desmos graph, with labeled $f(x)=Ax^4+Bx^3+Cx^2+Dx+E$, the general quartic equation, as well as its 2 inflection points $P$ and $Q$. A third point $R$ is labeled, which is the point that intersects the line between $P$ and $Q$ and $f(x)$. What we are interested in today is the ratio $\frac{PR}{PQ}$. Play with the graph below to vary $f(x)$ and see what happens to that ratio.

Quickly you will notice that for (most) non-zero $A$ values, $\frac{PR}{PQ}$ always remains at the rather famous constant, $\varphi=1.61803...$, the golden ratio. This may seem coincidental, but there is a rather nice way of proving that this ratio is exactly equal to the golden ratio.

The Golden Ratio

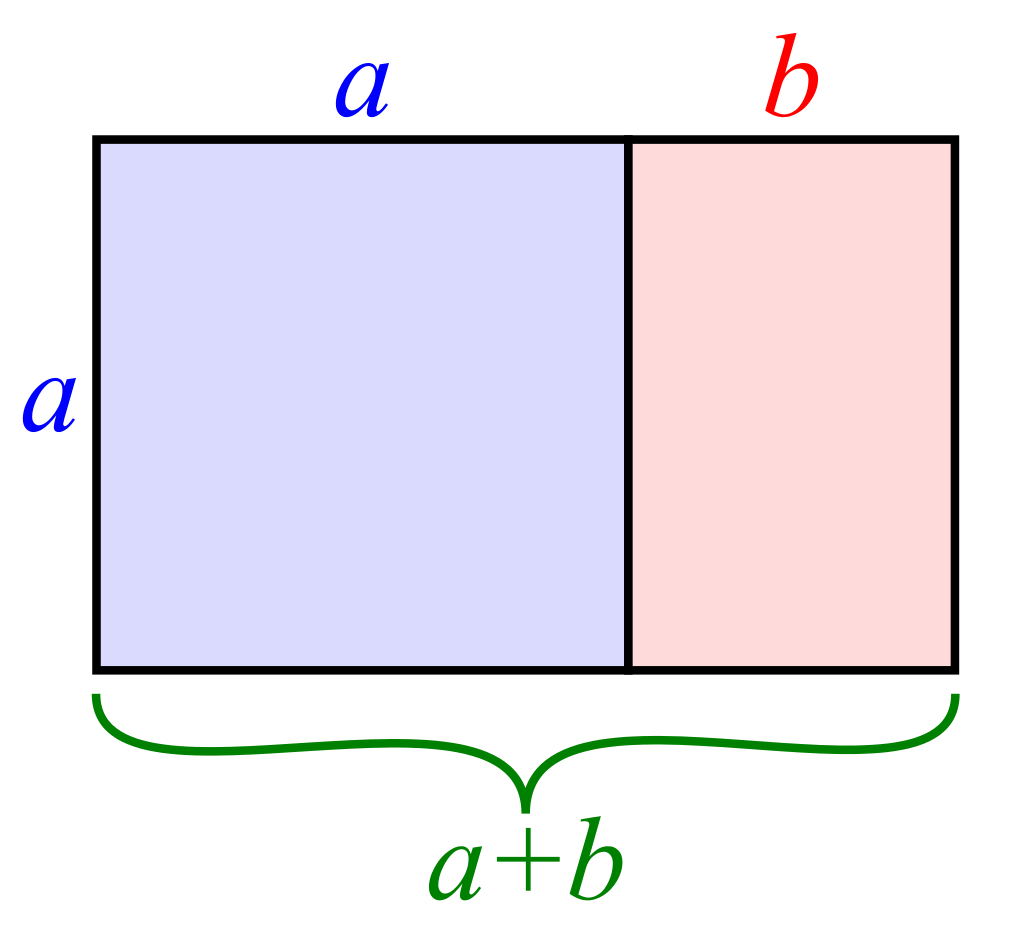

The classic definition of $\varphi$ comes from a specific geometric construction of a rectangle.

In this golden rectangle, there are two rectangles to focus on: the large one with aspect ratio $\frac{a+b}{a}$, and the smaller red one with aspect ratio $\frac{a}{b}$. The golden ratio is given by $\frac{a}{b}$ when the small red rectangle has the same aspect ratio as the larger rectangle (made up of the blue square and red rectangle). Letting $\varphi=\frac{a}{b}$, and setting the ratios equal to each other nets us:

$\large{\varphi = \large{\frac{1 \pm \sqrt{5}}{2}}}$

The positive solution to this quadratic is the more well known value $\varphi$. Taking some variations of the previous equations can net other interesting relationships that $\varphi$ pertains to. For example, taking the third line from the derivation of $\varphi$ nets a recursive, cyclic definition of the golden ratio. Expanding out the relation gives another famous definition of $\varphi$.

An infinite descending fraction solely containing 1s. Taking a variation of the fourth line also gives an interesting appearance of $\varphi$.

An infinitely nested radical solely containing 1s. Notice, however, that the solution to the golden ratio has a negative counter part as well: $1-\varphi=-.61803$. Although it may seem nonsensical to assign a negative value to many of the expressions we used in defining $\varphi$, this value holds many of the same properties that $\varphi$ holds on its own as well, and the reason we don't see it as often has to do with the volatility of the value in these iterated scenarios, but that's for another time.

The Proof

First, let's look at how to find the inflection points of a quartic. Inflection points are given by the quality that it's the point along a function where its concavity changes. I.e. if you look at the tangent lines along a curve as you vary the input $x$, the tangent lines' slopes will change. The inflection points are found when the slopes' behavior alters. Take the function $x^3$, for example.

Notice how as we let our value $a$ increase, the slope of our tangent line — the first derivative of $f(x)$ — decreases from $-1.5$ to $0$. But from $0$ to $1.5$, the slope begins to increase. This is all visualized in our graph $f'(x)$ which plots every point $x$ and the value of its slope at $f(x)$. One can clearly see $f'(x)$ tends in a downward manner initially, before rising again. And for $f'(x)$ to have a slope that's first negative (decreasing) then positive (increasing), it must have a slope of zero in between. So, our point where our concavity changes is when the slope of $f'(x)$ equals 0. In other words, when the second derivative $f''(x)=0$. Here we can see it clearly visualized at the solution $x=0$, which confirms all of our previous observations. Doing so for any general quartic nets us:

As this is a degree 2 polynomial, the quadratic formula quickly gives our two solutions for $x$ in general, which we will call $p$ and $q$.

This also explains why only most values of our constants have inflection points, as if the $9B^2-24AC$ term is negative, it results in an imaginary solution, meaning no inflection point is found within the real plane. With valid constants giving us solutions for our inflection points $P$ and $Q$ respectively, the line through them can quickly be written as:

The intersection point $R$ can be found solving for when $f(x)=g(x)$, or in other words, when $f(x)-g(x)=0$

$Ax^4+Bx^3+Cx^2+Dx+E-\frac{f(q)-f(p)}{q-p}(x-p)-f(p) = 0$

One can try to factor and work this out, but there is a much nicer approach that avoids working with this messy equation.

Transformations

If we limit our transformations to purely scaling and translating our graph, all of our ratios will remain equivalent. So if we can find a set of transformations to make our work easier, we will still be able to prove our initial proposition, but in a much easier way. To (re)start, we're going to define a new function $h(x)$ that takes $f(x)$, and scales and moves it around as follows:

This may seem arbitrary, but keeping in mind what $p$ and $q$ mean, this transformation alters the graph in a rather specific and useful way. First notice these two key components in our transformation:

This results in shifting the graph over to the left $p$ units and down $f(p)$ units. Or more clearly, it takes our first inflection point $(p,f(p)) \rightarrow (0,0)$, the origin. We'll refer to the origin as $P'$. Now, let's look at the remaining components of the transformation:

Multiplying $x$ by $q-p$ results in compressing the $x$-axis by a factor of $q-p$. So, the x coordinate distance between our inflection points is condensed from a length of $q-p$ to a length $\frac{q-p}{q-p} = 1$. Just to keep our scaling consistent throughout $f(x)$, we also scale the $y$-axis down by a factor $q-p$, so we add an extra factor of $\frac{1}{q-p}$. This factor is almost purely for aesthetic purposes, as you will see it will preserve the structure of our graphs and make it easier to see our scaled copy of $f(x)$ in $h(x)$. So, as the difference in $x$ coordinates between $P'$ and $Q'$ is 1, $Q'$ will be at $(1,h(1))$. $R'$ will retain its same definition as $R$, differing only in that it is on our newly transformed function.

Notice how the two inflection lines are parallel. That is due to that extra factor of $\frac{1}{q-p}$ in $h(x)$, but note that the math that follows is not dependent on it.

It's worth noting that we don't actually know any of the constants that shape our new quartic $h(x)=ax^4+bx^3+cx^2+dx+e$ as they don't change according to our scaling factors (notice the change in capitalization; these new constants for $h(x)$ is separate and different to those of $f(x)$). However, we do know the solutions to $h''(x)=0$. Instead of using our function to find its second derivative like we did in our original approach, we are working backwards from our second derivative to narrow in on our function. Since we know where our inflection points are at, we can rewrite our $h''(x)$ as a product of factors.

The factor of $12a$ comes from the leading term when taking the second derivative of any general quartic, as we saw in the original attempt to prove this. Expanding this expression and integrating twice gives us:

Notice I didn't add a new constant after the second integration, as that is equivalent to the $y$-intercept, which we know to be at $(0,0)$. Now that we have $h(x)$ in terms of itself, separated from $f(x)$, we can easily find the coordinates of $Q'$ and find $h(1)$.

Now we can create a new secant line $g(x)$ to pass through our two inflection points, $P':(0,0)$ and $Q':(1,b-a)$.

Now we can continue using our original method, which is to find all solutions to $h(x)-g(x)=0$. Only this time, our transformations should net a cleaner equation.

That $ax$ we factored out is our solution at $x=0$, or $P'$, which we used to construct the line in the first place. Similarly, because we used $Q'$ to construct the line as well at $x=1$, we can factor out an $x-1$ as well.

That last factor is the exact quadratic that we derived to define the golden ratio. Knowing that, we now have all of our solutions to the intersection points between our quartic and secant line.

The negative solution to the golden ratio here is the fourth point of intersection at $S:(s,h(s))$ with $s<0$. Now the last thing to note is that our 3 points of interest, $P'$, $Q'$, and $R'$, are all collinear. So, they can be thought of as a projection of the $x$-axis to a sloped line that scales how far they are spaced apart. However, since this is multiplicative, the ratios will be the same, so we only need to look at the ratios between their $x$ coordinates.

You can also quickly find other ratios of different lengths and find other interesting connections. Take $\frac{PQ}{QR}$, for example.

If you look at our defining quadratic $\varphi^2-\varphi-1=0$, it can be rewritten as $\varphi(\varphi-1)=1 \rightarrow \varphi=\frac{1}{\varphi-1}$. Completing our expression gives us:

Just as our golden rectangle previously foretold.