Irrational numbers are a bit strange to think about. In the sense, they were the first "new" type of number to really challenge early and young mathematicians. We have the natural numbers $\mathbb{N}$ like $\{0,1,2,3,\cdots\}$. From there, we then include the negative numbers $\{ \cdots,-2,-1,0,1,2,\cdots \}$ to have the integers $\mathbb{Z}$, that can be used to represent absences of quantities and additive inverses. From there, we can consider the in-between quantities of fractions, also known as the rationals $\mathbb{Q}$. For a while, this is what we thought all there was to numbers. Pythagoras and the Ancient Greeks famously thought there was no number that wasn't rational. They had this notion of increasing inclusion of numbers $\mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q}$, and that was the upper limit.

As we now know, this clearly isn't the case. We've talked about irrational numbers a little bit before, specifically on how $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational. It might be worthwhile going over the proof again:

Claim: $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational.

Proof: Suppose that $\sqrt{2}$ is not irrational. Therefore it is rational, and can be written as $\sqrt{2} = \frac{p}{q}$ where $p$ and $q$ are distinct coprime numbers (i.e. they don't share any factors in common; this is a way of sayiing that there is a unique way of writing $\sqrt{2}$ as a fraction in lowest terms). Squaring both sides and moving terms around, this equation becomes $2q^2 = p^2$. Therefore, $p^2$ is even, since it will always have a factor of 2 according to the lefthand-side of the equation. If $p^2$ is even, then $p$ is also even (if you're unsure of this fact, try some test cases and proving it!). Since $p$ is even, then let's rewrite it as $p=2n$. Plugging this into our equation yields: $2q^2 = p^2 = (2n)^2 = 4n^2$. Dividing both sides by 2 gives us $q^2 = 2n^2$. Similar to before, the equation implies that $q^2$ and hence $q$ is even due to that factor of 2 on the righthand-side. But this is a contradiction! $p$ and $q$ cannot simultaneously both be coprime and even (share a factor of 2). Hence, our initial assumption that the $\sqrt{2}$ is rational is wrong, and allows us to conclude that $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational. $\blacksquare$

This proof is pretty well-known, but to me, it's not necessarily obvious. Sure, in retrospect after knowing the proof, it might seem like a good direction to go in and get a contradiction within that rational assumption. But even then, it's a pretty clever proof.

I mention this, since I was recently thinking about an arguably more famous irrational number: $\pi$. A number studied forever that manages to appear in random sums, integrals, and expressions it has no right being in, it's no surprise it is one of the few symbols of math that transcends pop culture. And despite that, before writing this, I couldn't explain or prove why it is irrational. $\pi$ is geometric at heart, and translating to number-theoretic contexts just didn't seem to make sense. But along the way of finding out its proof (that stumped many before me), there is much to unpack about not just about $\pi$, but irrational numbers on the whole.

If you care for only the proof that $e$ and $\pi$ are irrational, skip here. Otherwise, follow through the table of contents for whatever you're looking for.

Decimal Expansions

The existence of irrational numbers actually implies a lot. For one, there are infinitely many more irrational numbers than rationals. With the classic diagonal argument, we can see that there are not any "more" rationals than integers or naturals. The irrationals are what make the real numbers uncountable. A way we can see that is through decimal expansions: all irrational numbers have non-repeating decimal expansions. So now if you imagine constructing a random number $0.142346\dots$ by picking a random number 0–9 at each digit, the chance of landing a repeating decimal is extremely unlikely.

Claim: A number is rational if and only if it has a terminating or repeating decimal expansion.

Proof: $(\Rightarrow)$ The easiest way to see this is through long division. If we have a rational number $\frac{p}{q}$ with $q \neq 0$, then at every step in the long division, we have $q$ possible remainders (being $0,1,2,\cdots,q-1$). If the remainder is 0 at any point, then we are done with the divison algorithm and the decimal expansion terminates (this it the case of 0 being the repeating portion of the decimal). If the remainder is never 0, after $q+1$ steps in the division algorithm, we will get a remainder we have already seen before, and so the division algorithm will keep producing the same digits in order we have seen before from that remainder. Hence the decimal expansion repeats.

$(\Leftarrow)$ Say we have a number $x = a.d_{1}d_{2}\cdots d_{n} \overline{d_{n+1} \cdots d_{n+m}}$ that has integer part $a$, $n$ pre-repeating decimals (each $d_i$ is a digit of the number), and $m$ repeating decimals (indicated by the overline). Then we can left-shift the non-repeating number by multiplying by a power of 10:

Since the decimals repeat after an additional $m$ digits, we can shift it further to get another similar looking number:

Now we can subtract equation $(1)$ from $(2)$ to eliminate the repeating decimal portion:

Now, see that since we have removed the decimal/fractional part of the numbers in that subtraction, the righthand side of the equation is an integer, call it $N$. Then we can solve for $x$ and see that

is a quotient of two integers, and so rational.

So if we want to use real numbers with decimals as we normally do, we need our non-repeating decimals to correspond to something. These are our of course our irrationals. But let's be clear exactly what non-repeating means. It's frequently unjustifiably said that since $\pi$ is irrational, it contains every single string of numbers ever conceived, and hence contains exactly the time and date you were born, you will die, and a copy of every book ever written. This is unknown. Just consider the non-repeating decimal that only contains 0s and 1s

Clearly this does not repeat, but certainly also does not contain all possible strings of numbers; it does not even contain all strings of 0s and 1s.

In a sense, too, the irrationals are also necessary for us. Without the irrational numbers, obviously we do not have all the real numbers, but the irrationals are necessary to fill in the gaps and holes left by the rationals to make the real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ as useful as they are. For example, a key property of the reals is that every subset of the reals that has an upper bound, in fact has a least upper bound. That is, for a subset $A \subset \mathbb{R}$ such that $\exists x \in \mathbb{R} \ \forall a \in A \ a \leq x$ (i.e. $x$ is an upper bound), there exists $\ell \in \mathbb{R}$ that is less than or equal to all possible upper bounds $x$. The rationals don't have this property: $\{ x \in \mathbb{Q} \ | \ x^2 < 2 \}$ has upper bounds in $\mathbb{Q}$, but not a least upper bound; we need irrationals and $\sqrt{2} \in \mathbb{R}$ to do this.

Completeness and the Variety of Irrationals

The irrationals, in this way, are integral to the real numbers. Not just in the sense that we have to include them, but in that they complete the real numbers. That least upper bound property we discussed above is what is referred to as the completeness of the real numbers (which can be an axiom or property derivative of other axioms, but either way is what characterizes the reals).

And yet, despite their utility, irrational numbers are still pretty mysterious. We know all rational numbers take on a certain form of $\frac{p}{q}$. Even complex numbers all reduce to some $a + bi$. But irrational numbers can take on any number of forms.

- Taking the square root of any non-square number is irrational

- The golden ratio $\varphi$ is irrational

- $e = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} \left(1+\frac{1}{n} \right)^n = \sum_{n = 0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n!} \approx 2.71828\cdots \ $ is irrational

- $\pi$ as the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter is irrational

Irrational numbers can pop up almost anywhere. Though, we might be getting a bit ahead of ourselves. We have a sort of "standard form" of irrational numbers given by our decimal expansions and our above claim: a number is irrational if and only if it has a non-repeating decimal part. But it's not like we can a priori check a decimal expansion is infinite to prove a number is irrational; it's usually shown that infinite decimal expansions are a consequence of irrationality.

Continued, Infinite, and Reasonable Fractions

So, while we showed that we in theory need irrational numbers, in practice representing them and using them seem far more tedious and annoying to work with.

And further, if you're just an engineer, astronomer, or even a mathematician that needs some concrete number to work with, rational numbers get us most of the way there for what we need. Why not just take some arbitrary decimal cut off? Most people only know $\pi$ up to $3.14$ anyway.

$3.14$ is pretty good, but an arguably better approximation is the famous $\frac{22}{7} \approx 3.14286$. Sure, it might be further off from $\pi$ than $3.14$, but it is a rather simple fraction that can make calculations easier and more convenient. You could go even further and get $\frac{355}{113} \approx 3.1415929$ which is good up to 6 decimals. Can we get any better?

So before we get any further in directly discussing irrationals, let's take a minute to talk more about rational numbers and their relationship with irrationals. From this, we'll see another nice property of irrational numbers that will help us along our way in a similar, but stronger way compared to decimal expansions.

Repeating Decimals $\Leftrightarrow$ Rationals

We alread proved that repeating and terminating decimals correspond to some rational number. So as a first step, it might be worth thinking about how we might go to and from fractions and these nice decimals before considering how we might do something with the weird and infinite decimals of irrationals.

Finite decimals are easy: just take the least power of 10 in it's decimal expansion and put it in the denominator of the digits. $.5 = \frac{5}{10^1} = \frac{1}{2}$, and $1.562782 = \frac{1562782}{10^6}$. Not particularly helpful.

If we have a repeating decimal, it's slightly trickier, but our proof above showing they are rational essentially tells us how to do the conversion.

- Consider the number $x = 2.642857 \overline{142857}$

- Using the above notation, $a=2$, $n=6$, $m=6$

- So $N = 10^{6+6}\cdot 2 + 642857142857 - (10^6\cdot 2 + 642857)$

- All together, we get that $x = \frac{N}{(10^6 - 1)10^6} = \frac{37}{14}$

You can also use geometric series to get the same answer, using the fact that the repetitions in the decimal are all separated by a ratio of $10^{-m}$ (for example, $0.\overline{142857} = 10^{-6} \cdot \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}142857\cdot 10^{-6n}$, and since $10^{-6}<1$, we get that it's equal to $10^{-6} \cdot 142857\cdot \frac{1}{1 - 10^{-6n}} = \frac{142857}{999999} = \frac{1}{7}$).

Though, we should expect that we can get these exact rationals since we already proved that finite and repeating decimals all are rational.

Rational Approximations

Now irrational numbers, on the other hand, by definition, will not have a rational form. So now we will actually need rational approximations. But finding those approximations, is not particularly easily. In particular, for irrational $x$, we want to find a rational $\frac{p}{q}$ such that $\left| x - \frac{p}{q} \right| < \epsilon$. At the very least, we know such rationals exist for any $\epsilon > 0$, since the rationals are dense in $\mathbb{R}$; there is always a(n infinite amount of) rational(s) in the interval $\left( x - \epsilon, x + \epsilon \right)$.

But we don't want to waste our time with "bad" approximations. Notice that for any denominator $q$, we can find a $p$ such that $\left| x - \frac{p}{q} \right| \leq \frac{1}{2q}$. This is just a result that if we divide the real numbers into intervals of size $\frac{1}{q}$, our number $x$ will fall in one of them and be closer to one side of the interval than the other.

It turns out though, we can find approximations that are far more "efficient" and get us much closer to our irrational number than just $\frac{1}{2q}$ for their denominator $q$.

Dirichlet's Approximation Theorem: $\forall x \in \mathbb{R}$ and $\forall N \in \mathbb{N}$, there are integers $p$ and $q$ such that $0 < q \leq N$ and $\left|qx - p \right| < \frac{1}{N}$.

As a consequence, we then have rational approximations $\frac{p}{q}$ that get us within $\frac{1}{q^2}$ of our irrational $x$ since $q\leq N$ implies

Proof: Pick $x\in \mathbb{R}$ and $N \in \mathbb{N}$. We will prove this using the Pigeonhole Principle. Note that any integer $n$ can be written as a fraction with any denominator $k$ as $\frac{nk}{k}$. So all we care about is approximating the fractional part of $x$, call it $\{x\} \in [0,1)$. Now divide the interval $[0,1)$ into $N$ equal subintervals of length $\frac{1}{N}$ i.e.

Now consider the set of $N+1$ numbers $kx$ for $0\leq k \leq N$, and in particular their fractional parts $\{kx\}$. By the Pigeonhole Principle, at least two of these fractional parts $\{k_1 x\}, \{k_2 x\}$ lie in the same $\frac{1}{N}$-subinterval of $[0,1)$ (without loss of generality, we can pick $k_1 > k_2$).

Note, we can write $\{kx\} = kx - \lfloor kx \rfloor = kx - j$ for some interger $j$. So if two fractional parts lie in the same subinterval, then what we have is

So if we let $q = k_1 - k_2$, and $p = j_1 - j_2$, then we have $0 < q \leq N$ and

which is exactly what we wanted to show.

Also, it's worth noting that there are infinitely many of these approximations, despite this just being an existence proof of at least one such pair $p,q$ that bound $\left|x - \frac{p}{q} \right| < \frac{1}{q^2}$. This can be quickly noticed since for a given $N_0$, Dirichlet's theorem says that there is at least one pair of $p_0,q_0$ such that $\left| q_0x - p_0 \right| < \frac{1}{N_0}$. But then, if we increase $N_0$ to $N_1$ large enough such that $\left| q_0x - p_0 \right| \geq \frac{1}{N_1}$, then Dirichlet's theorem ensures that there is some new pair of numbers such that $\left| q_1x - p_1 \right| < \frac{1}{N_1}$. And we can continue this forever.

As an interesting aside, this can also be used to show that rationals are in some ways worse than irrationals at being approximated by other rationals. Of course, if we "approximate" a rational with itself, it trivially holds that it is the "best" approximation. But concretely, if we have a rational $x = \frac{a}{b}$ and another rational $\frac{p}{q} \neq x$, then we get that

In particular, since $p,q,a,b$ are all integers, so would that difference above be, and so we can conclude that $|pb - qa| \geq 1$. So all together,

which is bounded away from 0, regardless of $q$. Which shouldn't be that surprising thinking through that $p,q$ are integers so that difference in distance should only have a non-integer part that is exactly proportional to the denominator $\frac{1}{b}$.

Best Rational Approximations

Dirichlet's Approximation Theorem tells us that we have stronger candidates than others for rationally approximating irrationals. Which is great and all, but can we give a more specific criterion to single out these "better" approximations? Or at the very least, approximations that we would prefer using?

We won't use the approximation that Dirichlet's Theorem would suggest above, as in using something "efficient" that gets us closer to the number we are approximating more than we'd expect it to. And besides, our proof above doesn't actually tell us how to find these good approximations since we have no control for our denominator $q$, but rather only an upper bound for $q$ with our choice of $N$. In particular, it also doesn't tell us how good our approximations are to other Dirichlet approximations; it could be the case that one approximation from Dirichlet's theorem is better than another despite having a smaller denominator (and so is in some way more preferable).

Probably the easiest metric of a best rational approximation of a number in this case would be that it is the best approximation for the smallest denominator found yet. Ideally, we want to work with "simple" fractions (i.e. with small denominators). So we say a rational approximation $\frac{n}{d}$ for a real number $x$ is best if $\frac{n}{d}$ is closer to $x$ than any other fraction with denominator less than $d$. If you want something more concrete, $\frac{n}{d}$ is a best approximation for $x$ if

To really get the point across, $\frac{p}{q}$ is a best rational approximation if it is not possible to get a better approximation using a smaller denominator. This is part of the reason why $\frac{22}{7}$ is so convenient to approximate $\pi$ as it is still a rather simple and easy-to-work with fraction, but is in a sense better than any possibly simpler fraction. Again, this is great to have, but we still don't have a way of finding these approximations any better than just brute force checking every other simpler fraction.

To find these approximations, we'll have to take a slight detour that perhaps is the closest link between representing any real number with rationals that you might have seen before.

Continued Fractions

Consider one of our favorite irrational numbers that we might want to approximate: $\sqrt{2}$. Before trying to find approximations or anything, notice that $\sqrt{2} - 1 = \frac{1}{1 + \sqrt{2}}$.

Now hold on. We just found that $\sqrt{2} = 1 + \frac{1}{1 + \sqrt{2}}$. If $\sqrt{2}$ equals that fraction on the righthand side, then we can just replace an instance of $\sqrt{2}$ with that same fraction:

And again:

And can keep doing this forever:

This is a continued fraction for $\sqrt{2}$. This particular one is the canonical or simple continued fraction for $\sqrt{2}$ since all the numerators are 1. The generalized continued fraction allows for any numerator. Perhaps an even more famous continued fraction is that for the golden ratio $\varphi$:

As shorthand, simple continued fractions are sometimes written as $\sqrt{2} = [1;2,2,2,2,\ldots]$ to indicate the coefficients. So likewise, $\varphi = [1;1,1,1,1,\ldots]$.

Properties of Continued Fractions

Working with things that look like rational numbers should key us into that this is closer to where we want to be looking. And like decimals, continued fractions gives us a nice dichotomy between the rational and irrational.

Claim: A number is rational if and only if its simple continued fraction representation is finite.

Proof: $(\Leftarrow)$ If the continued fraction is finite i.e.

Then we can just collapse the continued fraction by creating common denominators and simplifying with normal fraction rules, showing $x$ is rational.

$(\Rightarrow)$ The idea is we'll continuously separate our fraction into its integer and fractional parts, and continue to reduce the fractional part. As an example,

If $x = \frac{p}{q}$ is rational, then we can repeatedly apply the division algorithm to create our continued fraction. So write $p = a_1 q + r_1$ for $0\leq r_1 < q$. Hence, we can write $\frac{p}{q} = a_1 + \frac{r_1}{q} = a_1 + \frac{1}{\frac{q}{r_1}}$. Again, we can repeat the division algorithm and write $q = a_2 r_1 + r_2$ for $0 \leq r_2 < r_1$.

To put it more neatly, write the following division algorithm steps:

Note since $r_1 > r_2 > \cdots > r_{n-1}$ form a sequence strictly decreasing and non-negative integers, this process must eventually terminate with all $r_m = 0$ after a certain point in a finite number of steps (this is what justifies using the division algorithm to find the GCD of two numbers). Once our algorithm terminates in a finite number of steps (this is what keeps our continued fraction finite), it's just a matter of writing out the continued fraction:

and we're done.

So this actually gives us a direct proof that $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational with its continued fraction: its simple continued fraction is infinite, and so it must be irrational.

More on Irrational Continued Fractions

Let's go back to our proof that all rational numbers have finite continued fraction expansions. Another way we can see this fact is by constructing continued fractinos for irrational numbers, and we do so in almost the exact same way we did for rationals. The idea in using the division algorithm is that we separate our number $x$ into its integer and fractional component, and then invert the fractional component (which is less than 1, so inverting it gives us a number greater than one to keep separating into integer and fractional parts). I.e. first write

and then repeat this exact writing process on $x - \lfloor x \rfloor$. But since $x - \lfloor x \rfloor$ is also irrational, and so will all future denominators at each step. The only way this process terminates is if our step $x - \lfloor x \rfloor = 0$ which is rational, and hence can't happen.

Claim: Let $x$ be irrational. Let $x_0 = x, \ a_k = \lfloor x_k \rfloor, \ x_{k+1} = \frac{1}{x_k - a_k}$. Then for all $k$

Proof: This follows immediately from our construction above: separate the integer part and invert the fractional. It clearly holds for $k=0$, since $x = x_0$. Say this holds for $k$. Then $x_{k+1} = \frac{1}{x_k - a_k} \Rightarrow x_k = a_k + \frac{1}{x_{k+1}}$ and so

Then it is not too hard to show that we can extend this to the infinite continued fraction in the way we'd want to.

Claim: $[a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots] = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} [a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n] = x$

Before we continue into the infinite, we'll need some tools about the finite first that we will extend with limits. The truncated continued fractions of $x$ called the convergents of the continued fraction. The nth convergent of a continued fraction is

A convergent is just the initial segment of the continued fraction up to the $nth$ denominator. One useful fact we will need is the recursive formula for the numerator $p_n$ and denominator $q_n$ of these convergents (since the direct formula can get very complicated in simplifying it).

Lemma: For an infinite continued fraction $[a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots]$ with $a_i > 0 \ \forall i > 1$, let $c_n = \frac{p_n}{q_n}$ be the nth convergent. We then have the following recurrence:

Proof: We'll prove this inductively. Note when I equate two fractions here, I mean to literally equate the numerators and denominators just as shorthand to show the two recursions at once (and simultaneously link it back to the convergent directly).

Base Case: We just quickly check this $c_0 = \frac{a_0}{1} = \frac{p_0}{q_0}$. $c_1 = a_0 + \frac{1}{a_1} = \frac{a_1 a_0 + 1}{a_1} = \frac{p_1}{q_1}$.

Inductive Step: Say this is true for $c_n = \frac{p_n}{q_n} = \frac{a_n p_{n-1} + p_{n-2}}{a_n q_{n-1} + q_{n-2}}$. Now consider $c_{n+1} = [a_0, a_1, \ldots, a_n, a_{n+1}]$. Note we can obtain $c_{n+1}$ from $c_n$ by replacing $a_n$ with $a_n + \frac{1}{a_{n+1}}$. That is, we can do a substitution trick like we did before, and write $c_{n+1} = [a_0, a_1, \ldots, a_n + \frac{1}{a_{n+1}}]$. Fortunately, by the inductive hypothesis, we have our numerator and denominator of $c_n$ in a form that is dependent on $a_n$ and makes this substitution possible (note that $p_{n-1}$, $p_{n-2}$, $q_{n-1}$, $q_{n-2}$ don't depend on $a_n$, so they remain unaffected by this substitution).

Giving us exactly what we wanted.

These recursions give us some very useful ways of characterizing convergents, since without them, it isn't hard to imagine how complicated the numerators and denominators might become when trying to collapse the continued fraction.

Claim: $p_{n-1} q_n - q_{n-1} p_n = (-1)^n$

Proof: As expected, we'll use induction:

Base Case: For $n=1$, we get $p_0 q_1 - q_0 p_1 = a_0 a_1 - 1 \cdot (a_1 a_0 + 1) = -1$. Inductive Step: Suppose this is true for $n$. Then using our recursions, we can show this holds for $n+1$:

This fact also then immediately tells us that $\gcd (p_n, q_n) = 1 $ and that they are coprime, so $c_n = \frac{p_n}{q_n}$ is always in lowest terms. It also gives us a nice relation between adjacent convergents:

This fact that $c_n - c_{n-1} = \frac{(-1)^{n+1}}{q_n q_{n-1}}$ will get arbitrarily small also shows they form a Cauchy sequence (the formal proof is just using this bound with the triangle inequality) and hence converge $\lim\limits_{n\to\infty} c_n$ exists. Below we'll show that they converge to the limit we expect.

Taking a minute to give some terminology and the above recurrence will help us in the future.

Claim: Using the $a_i$, $x_i$ defined above, $[a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots] = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} [a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n] = x$

Proof: As with any question about infinity, we look at the partial, in-between steps and consider the formal limit. That means our convergents $c_n$ i.e. we want to show $\left| x - c_n \right| = \left| x - \frac{p_n}{q_n} \right| \rightarrow 0$.

First, note clearly the $x_n$ is irrational for all $n$. Second, we'll show $a_n > 0$ for all $n$ so we can use our recursive formula of convergents above. This follows because our algorithm essentially takes the fractional part of our number (which is less than 1), and inverts it (making it greater than 1) at the next step: since $a_k = \lfloor x_k \rfloor$, we have $a_k < x_k < a_k + 1$ (we get a strict lower inequality by the irrationality of $x_k$). So $0 < x_k - a_k < 1$. Hence, $x_{k+1} = \frac{1}{x_k - a_k} > 1$, and therefore $a_{k + 1} = \lfloor x_{k+1} \rfloor \geq 1$.

So we can use our recursive formulas for convergents we proved above. Also using our "finite" continued fraction from before, we can write

Therefore,

The last equality we showed above with our recursions. Taking absolute values,

Also, $x_{n+1} > \lfloor x_{n+1} \rfloor = a_{n+1}$, so $x_{n+1} q_n + q_{n-1} > a_{n+1} q_n + q_{n-1} = q_{n+1}$:

Next, note that $q_n \geq n$ for $n \geq 1$:

Lemma: $q_n \geq n$ for $n \geq 1$.

Proof: $q_1 = a_1 \geq 1$ as shown earlier, so we have a base case established. Say $q_k \geq k$ for $k\leq n$. Then $q_{n+1} = a_{n+1}q_n + q_{n-1} \geq 1 \cdot n + n-1 \geq n+1$. $\blacksquare$

Finally,

Giving the limit

So we're actually justified in using these infinite continued fractions in the way we want to, and generate them in a semi-algorithmic way:

I say semi-algorithmic since the way I presented above already relies on having the exact value of $\pi$ in decimal, which can be arguably harder to find. It's good enough to get us as many coefficients as we'll practically need, but we'll address this problem later.

Best Rational Approximations

Now the reason we went through all this trouble is because continued fractions have the surprising ability to generate best rational approximations systematically. Remember, we say a rational approximation $\frac{n}{d}$ for a real number $x$ is best if $\frac{n}{d}$ is closer to $x$ than any other fraction with denominator less than $d$.

Definition: We say $\frac{p}{q}$ is a best rational approximation for $x$ if

Now here's the remarkable fact:

Theorem: Write an irrational number $x = [a_0; a_1, a_2, \ldots]$ as its continued fraction expansion. Then for any convergent $c_n = \frac{p_n}{q_n}$ and any rational $\frac{a}{b}$ with $b < q_{n+1}$, then $\left| q_n x - p_n \right| \leq \left| bx - a \right|$.

This is actually a stronger statement, since it's not only a best rational approximation, but it is also a better rational approximation than some denominators greater than $q_n$. It should not be surprising that $q_{n+1} > q_n$ for all $n$ (just think about the process involved in collapsing a continued fraction; or show by induction with the recursion formulas). But what our claim says is that for not only rational approximations of denominator less than $q_n$, but also for some denominators greater than $q_n$, $\frac{p_n}{q_n}$ is still a better approximation for $x$. Which is surprising, since that would mean even if we divide the real numbers into smaller boxes, sometimes our numbers will be closer to the edges of the bigger box. It's like saying that a steak knife can get you a more precise cut than some X-Acto knives.

Proof: Let $\frac{a}{b}$ be a rational number in lowest terms such that $b < q_{n+1}$. We'll also assume $a \neq p_n$ and $b \neq q_n$ (since then we clearly have equality). We'll rewrite $a,b$ in terms of new numbers $r,s \in \mathbb{R}$ that we define by the following system of equations:

$r,s$ exist since that system of equations is equivalent to the matrix system

and we showed that the determinant $p_n q_{n+1} - q_n p_{n+1} = (-1)^{n+1} \neq 0$ and so is invertible. Now if we solve for $r,s$ (either with matrices or directly), we see that

So $r,s$ are integers.

Claim: $r,s \neq 0$.

Proof: If $r = 0$, then $q_{n+1}a = p_{n+1}b$. But since $p_{n+1}$ and $q_{n+1}$ don't divide each other (we proved earlier they were coprime), we have $q_{n+1}$ divides $b$, contradicting the assumption that $b < q_{n+1}$. If $s=0$, then we have $\frac{a}{b} = \frac{p_n}{q_n}$ which we already excluded in our assumptions. $\blacksquare$

Claim: $r$ and $s$ have opposite signs.

Proof: We'll just check the two cases.

- If $s > 0$, then $s \geq 1$. Therefore $sq_{n+1} \geq q_{n+1} > b$, and thus $b = rq_n + sq_{n+1}$ implies that $rq_n = b - sq_{n+1} < 0$. Since $q_n > 0$, we must have $r<0$.

- If $s < 0$, then $-sq_{n+1} > 0$. Hence we have $rq_n = b - sq_{n+1} > 0$. Thus $r > 0$. $\blacksquare$

Claim: $q_n x - p_n$ and $q_{n+1} x - p_{n+1}$ have opposite signs.

Proof: Note we saw earlier that the difference between consecutive convergents alternate in sign:

That is, the convergents take turns being greater or lesser than the previous convergent. What this means is that our convergents alternately overshoot and undershoot its limit $x$ (in particular, knowing that $c_0 = \lfloor x \rfloor < x$, the even convergents undershoot and the odd ones overshoot). So in particular, for all $n$, we have

If we take the first case, then the first inequality gives $0 < q_n x - p_n$ while the second one gives $q_{n+1} x - p_{n+1} < 0$, so they're of opposing signs. Similarly the second case gives the same. $\blacksquare$

Claim: $r(q_n x - p_n)$ and $s(q_{n+1} x - p_{n+1})$ have the same signs.

Proof: This is just something you can check by cases. The opposing parity of $r,s$ and of $(q_n x - p_n), (q_{n+1} x - p_{n+1})$ cancel each other out. $\blacksquare$

Finally, putting this last fact to work, we get

We can separate the absolute values in the 3rd equality since they have the same sign, and the last inequality comes from the fact that we showed the integer $r \geq 1$.

For completeness sake,

Corollary: Each convergent $c_n = \frac{p_n}{q_n}$ is a best rational approximation for $x$.

Proof: Suppose otherwise, so that there $\exists \frac{a}{b}$ such that $b \leq q_n$ with

Multiplying these inequalities together gives

But this contradicts our theorem as $b \leq q_n < q_{n+1}$. $\ \blacksquare$

The Most Irrational Number

If you want to approximate $\pi$, we now have a good way of doing so: take some convergent of the continued fraction. Looking at the first couple,

which are some of the more famous approximations of $\pi$. Note, if you do want to get really good approximations, making the last term in a convergent large is ideal. Notice how much closer we got with $c_2$ compared to $c_1$, and that is precisely because 15 is (relatively) much bigger than 7. These large coefficients get multiplicatively bigger as we simplify the convergent, giving us a rather large denominator $q_n$ that more finely dices the real numbers for us to approximate with. $\pi$ has a lot of these large numbers in its continued fraction expansion, giving us good convergents to create these surprisingly accurate best rational approximations.

This also means, if you care about small denominators, it's worth stopping one before a large number (i.e. at 7 instead of 15, or 1 instead of 292); if you need such a large number to generate a new best rational approximation (and get a really big denominator), then it must have been that the approximation before it must have also been really good if you had to zoom in that much on the next step.

NOTE: we proved that all convergents are rational approximations, but the converse is not true! $\frac{13}{4}$ is also a best rational approximation for $\pi$, but is not generated through our convergents.

So, what if we minimize all the coefficients then? If we give no large numbers to stop at for our convergents, we'll be left with a number that is not easy to approximate at all. We know all the numbers are positive integers, so let's just set them all to 1 to minimize them:

We know this converges as we showed that the difference between consecutive convergents gets small (and so forms a Cauchy sequence), and as we saw before this is the Golden Ratio $\varphi$. We can also solve this directly if you wanted: if we set the value of the fraction to $x$

we can see that the boxed portion of the fraction is equivalent to the original, whole fraction, so we can substitute $x$ for the box.

$x^2-x-1=0$

Is precisely the quadratic that has roots at $\frac{1 \pm \sqrt{5}}{2}$ (we only admit the positive solution by since all our convergents are positive, and limits preserve weak inequalities, so the limit is non-negative).

So if we look at some of the convergets of $\varphi$, they're quite bad at approximating it (for reference, $\varphi \approx 1.618034$):

In fact, takes until $c_9$ to get 3 decimals correct. Remember, the first convergent for $\pi$ was already within 3 decimals.

Since $\varphi$ is so bad—in fact as we've demonstrated, the worst—to approximate rationally, it is often referred to as the most irrational number.

Relation to Dirichlet's Approximation Theorem

Recall, in our first little discussion about approximating irrational numbers, we spoke about Dirichlet's Approximation Theorem.

Dirichlet's Approximation Theorem: $\forall x \in \mathbb{R}$ and $\forall N \in \mathbb{N}$, there are integers $p$ and $q$ such that $0 < q \leq N$ and $\left|qx - p \right| < \frac{1}{N}$.

The more concrete result we got out of it was that we could have rational approximations $\frac{p}{q}$ that get us within $\frac{1}{q^2}$ of our irrational $x$, which is much better than our initial bound of being within $\frac{1}{2q}$ of $x$.

In our proof on the convergence of continued fractions, we actually say that our convergents actually satisfy this bound too. Look above in the proof, and we deduced that

and the final inequality comes from the fact that $q_{n+1} > q_n$. So, as we'd hope, our best rational approximations from continued fractions are also just outright good and efficient approximations.

In fact, we can usually do a little bit better.

Corollary: For irrational $x$ and for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$, at least one of the convergents $\frac{p_n}{q_n}$ or $\frac{p_{n+1}}{q_{n+1}}$ satisfy the inequality

Proof: Suppose this isn't true. Then

The second equality follows since $\frac{p_n}{q_n} < x < \frac{p_{n+1}}{q_{n+1}}$ or $\frac{p_{n+1}}{q_{n+1}} < x < \frac{p_n}{q_n}$. Say we're in the first case, then

and the $x$ terms cancel (similarly for the second case). The last equality is precisely the difference between two adjacent convergents we found earlier.

But we already know that $q_{n+1} > q_n$, so this can't hold, giving us our contradiction. $ \ \blacksquare$

It turns out the converse to this is in fact true:

Legendre's Theorem: If $x \in \mathbb{R}$, and $\frac{p}{q} \in \mathbb{Q}$ such that $\left| x - \frac{p}{q} \right| < \frac{1}{2q^2}$, then $\frac{p}{q} = c_n$ is a convergent of the continued fraction for $x$.

We won't prove this, but the proof can be found on the Wikipedia page.

Finding Continued Fractions

One problem I had with continued fractions originally was that there didn't seem to be a particularly nice way of actually finding them. It's nice that we have this very straightforward way of doing it by separating integer parts and inverting the fractional, but that already requires us to have calculated the decimal expansion of whatever number we're expanding. This makes it seem not as elegant and a bit clunky, so when I found this paper outlining another method, I had to look through it.

The accuracy of this method will still rely on having some level of floating point precision, but otherwise, I think it is a much nicer of going about finding continued fractions in a way that weaves in another natural approximation method. The idea lies within finding roots of functions in a way similar to Newton's method.

Say we want to find the continued fraction of the number $\alpha$. Further, assume that there is a twice differentiable function $f(x)$ such that $f(\alpha) = 0$. To get a rough idea of the algorithm, there are two facts we first must take note of.

1) The Mean Value Theorem: Given a function $f(x)$ that is differentiable on the interval $(a,b)$, the Mean Value Theorem states that $\exists c \in (a,b)$ such that

That is, there is a point that has a tangent with the same slope as the secant line between endpoints of the graph. So if we consider the interval between $(\alpha, t)$ where $f(\alpha) = 0$, we get that

Rearranging a little bit and letting $t= \frac{p_n}{q_n}$ be a convergent of $\alpha$, we can see that

2) Relating convergents and remainder coefficients: Recall in our proof that simple infinite continued fractions converge, we found that

where $\alpha_{n+1}$ is the "remainder" coefficient we get when calculating continued fractions i.e.

If we combine these two equalities, we get that

If we solve for $\alpha_{n+1}$:

This is great, since now we have a direct way of computing the coefficients $a_{n+1} = \lfloor \alpha_{n+1} \rfloor$. Further, the computation only requires knowing the evaluating the function $f(x)$ and the previous two convergents! This is the basis for the algorithm: we repeatedly compute values of $a_{n+1}$ by computing the remainder $\alpha_{n+1}$ with our convergents.

However, this only maintains equality for the value fo $c \in (a, \frac{p_n}{q_n})$. So what we do instead is approximate $\alpha_{n+1}$ with a reasonably close value. One value that works just fine is $\frac{p_n}{q_n}$ itself. So what originally was could be a hard problem of finding decimal expansions of $\alpha$ to do our separate-and-invert algorithm, now becomes a much more tractable problem in computing decimals in evaluating a function. Also this process is memoryless: it does not need anything more than the previous state two convergents to compute the next. Whereas if we wanted to refine our continued fraction with the old method, we would have to start from the very beginning and recompute everything.

Again, this still requires calculating something else to an arbitrary precision to get the correct continued fraction (and we still need to get the first two convergents manually as seed values). So in the case of $\pi$, we are calculating instances of $\sin(x)$, which in some ways easier. This gives a wide range of numbers we can now compute continued fractions for:

- For $\sqrt{2}$, we use $f(x) = x^2 - 2$

- For $\ln(n)$, we use $f(x) = e^x - n$.

- For $\pi^2$, we use $f(x) = \sin(\sqrt{x})$

- For $e^\pi$, we use $f(x) = \sin(\log x)$

Many other function compositions can lend to many other numbers that would seem otherwise hard to get continued fractions of.

For more details and a coded demo, check out this Python notebook that is set up to calculate the first 50 coefficients (as well as the convergents and their numerators and denominators) of the simple continued fraction for $\pi$.

Applications of Best Rational Approximations

Music Tuning

Approximating irrationals are convenient for nothing more than just that in most cases: convenience. But here's something that requires this irrational approximation.

We here sound and music intervals on an exponential scale. Given a note with frequency $f$, it's octave is the note with frequency $2f$. So obviously, they have a frequency ratio of 2:1. Since this, in a sense, is the simplest ratio we can have between notes' frequencies, the octave forms the basic ratio for end points in our musical scale. The more interesting notes are the ones between an octave with more complex ratios to the base frequency. Common intervals include a major third with a frequence ratio of 6:5 to the base note, or perfect fourth with 4:3. But perhaps the most famous and most recognizable is the perfect fifth with a ratio of 3:2. The theme to Star Wars famously opens with a perfect fifth.

As nice as these rational intervals are, they pose a slightly annoying problem: they are not (geometrically) evenly spaced, so they don't divide an octave into even steps. If you wanted to build a piano, this would make tuning each note very tedious, and make our notes feel a bit random without this consistent spacing.

If we wanted to divide an octave evenly into $n$ notes, that means we want to be able to find the corresponding frequency ratio of $2^\frac{1}{n}$ (remember, we hear sound exponentially, so hearing the next note up is equivalent to multiplying our base frequency by our desired ratio). But this number is irrational (proof is identical to our why $\sqrt{2} = 2^\frac{1}{2}$ is irrational)! So this runs into a different problem: we'll never be able to exactly get our rational frequency ratios for our intervals like the fourth or the fifth.

So we're at a crossroads: either we keep our rational frequency ratios for nice intervals and the octave isn't evenly divided, or we divide our octave evenly and never have a rational interval. So we compromise: we find a value of $2^\frac{m}{n}$ that closely approximates our ratios, and that value of $n$ tells us how many notes we divide our octave into.

Here's where we can use continued fractions and our best rational approximations. Since the perfect fifth is probably the most univerally harmonious interval, we'll try and approximate that first. Then, we note that

So if we can approximate $\log_2 (3/2)$ the best we can, we'll get a reasonable rational exponent that closely solves $2^\frac{m}{n} = \frac{3}{2}$. We can write out the first few numbers of the continued fraction by hand using our algorithm from before:

Looking at the first few convergents, we see that

Looking at our denominators, we get options of $n = 1,2,5,12,41,\cdots$. Using $n \leq 5$ gives too few notes in a scale, and $n = 41$ might be too many. So $n=12$ notes feels like a good in-between, and in fact is what we actually use on most pianos today: 7 white keys and 5 black per octave. (One interesting best approximation not found here is also $n=19$, which some might find a reasonable choice too)

Cryptography and Wiener's Attack

RSA is one of the most widely used cryptographic protocols used, protecting most of the internet's traffic today.

Here's a brief rundown how two people, Alice and Bob, would share secret messages (i.e. can only be read by the recipient) using RSA:

- Bob chooses two (ideally large) prime numbers $p,q$ and calculates $N = pq$, and an integer $e$ (called the encryption exponent). He then releases to everyone the public key $(N, e)$. This is how people will hide and encode their messages to Bob.

- To decrypt messages, we need we need the decryption exponent $d$ that satisfies $ed \equiv 1 \bmod \varphi(N)$. $\varphi(n)$ is Euler's totient function and returns the total number of integers less than $n$ that are coprime to $n$. We also need $\gcd(e, \varphi(N)) = 1$.

- The factorization of $N$ and $d$ are kept secret, and form the private key. This is what allows Bob and only Bob to decrypt messages.

- To encrypt a message $M$, Alice sends the ciphertext $C = M^e \bmod N$

- To decrypt it, Bob computes $C^d \equiv (M^e)^d \equiv M^{ed} \equiv M \bmod N$

The decryption equivalence follows by Fermat's little theorem, and is not too hard to verify (you can also check the Wikipedia page). Also, note that sometimes instead of $\varphi(n)$ people will also use the Carmichael function $\lambda(n)$. In our case, $\lambda(pq) = \mathrm{lcm}(p-1,q-1) \leq (p-1)(q-1)$ which maintains all the properties needed.

The security of RSA relies on the surprising asymmetry in factorization: given $p$ and $q$, calculating $N = pq$ isn't hard, but given an $N$ finding two numbers such that $N = pq$ is difficult. Without being able to factor $N$, the private key remains private and hence messages can't be stolen. At least, that's our idea—it's secure because we don't know how to factor numbers efficiently (at least, not without quantum computers). No one does. So we use RSA everywhere for that reason.

So if we could break it, that would be quite bad.

Wiener's attack exploits one thing that we didn't put much effort specifying: the decryption exponent $d$. If $d$ is chosen in such a way that it's small enough (specifically when $d < \frac{1}{3} N^{\frac{1}{4}}$) Wiener's attack can break through RSA. This, though, is a really small range of $d$. If we let $N$ be a number with 20 digits, $d$ can at most have 5 digits.

Some Preliminaries

First, note for (co)prime $p,q$, we have

This follows from a simple counting argument: the numbers that are not coprime to $pq$ are the multiples of $p$ and the multiples of $q$ less than $pq$, i.e. $1p, 2p, 3p, \cdots, (q-1)p$ and $1q,2q,3q,\cdots(p-1)q$. So there are $(p-1) + (q-1) = p + q - 2$ numbers not coprime to $pq$. There are $pq-1$ numbers less than $pq$. Hence there are

numbers coprime to $pq$. (also follows because $\varphi$ is multiplicative, so $\varphi(pq) = \varphi(p)\varphi(q)$ if $p,q$ coprime; think Chinese Remainder Theorem).

So if we know $p+q$ then we know $\varphi(N)$ and vice versa. If you're familiar with Vieta's fomrulas, these look a lot like expressions that appear in quadratics:

By the quadratic formula,

So if we know $N$ and $\varphi(N)$, we can recover $p,q$ without ever needing to go through the problem of factoring. $N$ is already public information in RSA. To find $\varphi(N)$, all we know about $\varphi(N)$ is $ed \equiv 1 \bmod \varphi(N)$. In other words, $ed = 1 + k \cdot \varphi(N) = 1 + k \cdot (p-1)(q-1)$ for some integer $k$. Therefore,

If we want to find $\varphi(N)$, what we really want to find is $k$ and $d$.

Second, we make the following observation:

- Let $N=pq$, $e$, and $d$ be given.

- Note $\varphi(N) = (p-1)(q-1)$.

- Also, $ed = 1 + k \cdot \varphi(N) = 1 + k \cdot (p-1)(q-1)$ for some integer $k$

- Dividing by $dpq$, we get $\frac{e}{pq} = \frac{k}{d} \cdot \frac{pq - p - q + 1 + \frac{1}{k}}{pq} = \frac{k}{d}(1-\delta)$ where $\delta = \frac{p + q - 1 - \frac{1}{k}}{pq}$

- Note $\delta < 1$ since $pq > p+q$ for all $p,q > 1$. So we get $\frac{e}{pq} < \frac{k}{d}$ by a small amount.

So we have $\frac{e}{N} \approx \frac{k}{d}$, so if we can guess approximations (should start ringing a bell) of $\frac{e}{N}$, we might be able to guess $\frac{k}{d}$.

Wiener's idea then is to use the convergents of the continued fraction for $\frac{e}{N}$ to get potential values of $\frac{k}{d}$, as those would give us nice rational approximations.

Example: Let $(N,e) = (90581, 17993)$ be our public key.

The first convergent $\frac{0}{1}$ does not give $k,d$ values to factor $N$ ($k=0$ is the real problem). But it can be checked that the next convergent $\frac{1}{5} = \frac{k}{d}$ does work, and gives the correct guess for $\varphi(N)$:

If we plug this into our quadratic from before, we get $p,q = 379, 239$ which correctly factors $N$.

Here are all the conditions necessary for this attack.

Wiener's theorem: Let $N=pq$ with $q < p < 2q$, and $d < \frac{1}{3} N^{\frac{1}{4}}$ such that $ed \equiv 1 \bmod \varphi(N)$. Given $(N,e)$, one can recover $d$.

Proof: First note that since $q<p<2q$, we have that $p+q - 1 < 3\sqrt{pq}$:

Recall that $\varphi(N) = (p-1)(q-1) = N - p - q + 1$. Combining this with our above inequality gives $\left| N - \varphi(N) \right| < 3\sqrt{pq} = 3\sqrt{N}$. Now also remember that $ed - k\varphi(N) = 1$, so we get that

$k\varphi(N) = ed - 1 < ed$, so since $e < \varphi(N)$ (the public key can and usually is chosen as such because modular arithmetic ensures there is one), we then must have $k < d$ for that equality to have any hope in working out. Therefore,

Since $d < \frac{1}{3} N^{\frac{1}{4}}$, we have that $9d^2 < N^{\frac{1}{2}}$. Hence,

By Legendre's theorem that we mentioned above, $\frac{k}{d}$ is equivalent to a convergent of the continued fraction for $\frac{e}{N}$. Also, $ed - k\varphi(N) = 1$, so $\gcd(k,d) = 1$, so $\frac{k}{d}$ is already in lowest terms. So not only is $\frac{k}{d}$ equivalent to a convergent, it is in fact the convergent with the same numerator and denominator.

Note that the bound on $d < \frac{1}{3}N^{\frac{1}{4}}$ was picked precisely to satisfy Legendre's theorem, to ensure it would be a convergent. Others have improved on this bound, and one we can clearly see that if we want $\frac{3}{\sqrt{N}} < \frac{1}{2d^2}$, we can let $d < \frac{1}{\sqrt{6}}N^{\frac{1}{4}}$.

Solving Pell's Equation

Pell's equation is the Diophantine equation (that is, we want integer solutions for it)

where $D$ is a non-square positive integer (for negative or perfect square $D$ since there are only the finitely many solutions $(\pm 1, 0)$ by considering the sign of the equation or factoring a difference of squares). Continued fractions and solutions to Pell's equations are surprisingly intertwined.

The key lies in the fact that there is a 1-to-1 correspondence between quadratic irrationals and repeating continued fractions. That is, if the coefficients in a continued fraction ever cycle, then the continued fraction can be written as $\frac{p + \sqrt{q}}{r}$ where $q$ is a non-square.

We won't get into it here, but here are some notes and a paper that fill in the details for quadratic irrationals and Pell's equation.

Pell's equation seems innocuous at first—just a genereic equation that people historically studied for one reason or another, but it is because of its general form that lends itself to the necessity of studying Pell's equation.

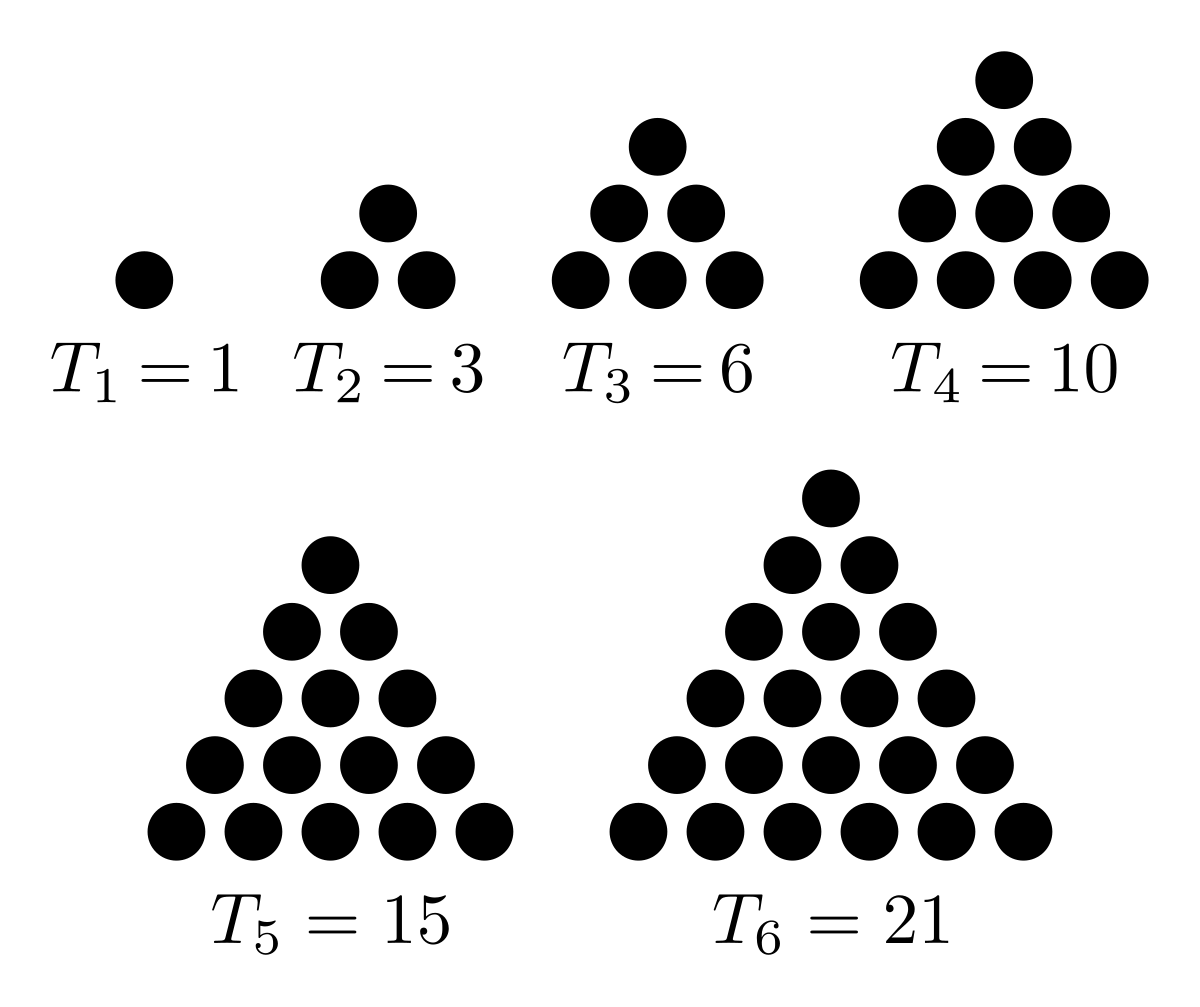

Question: The triangular numbers are $1, 3, 6, 10, \cdots, \frac{n(n+1)}{2}, \cdots $. Are any of these a perfect square?

The first 6 triangular numbers. Credit: Wikipedia

Solution: We are essentially solving $\frac{1}{2}n(n+1) = m^2$. Rewriting a little bit, we want to solve $(2n+1)^2 - 8m^2 = 1$. Let $x = 2n+1$ and $y = m$, we just need to find solutions to $x^2 - 8y^2 =1$. From the above results (that we did not cover), we can do that systematically with the continued fraction for $\sqrt{8}$.

For an absurd historical example of Pell's equation, here's one attributed to Archimedes.

The Original Proof of the Irrationality of $\pi$

We've gone through a few properties and interesting tidbits that characterize irrational numbers especially as it comes to computing and approximating them. These tools, especially of continued fractions, give a tool that can be used to deduce irrationality of numbers. In fact, the first proofs that $e$ and $\pi$ were irrational originally came from them. But I wanted to talk about them specifically because I want it to be clear jsut how little we actually know of irrational numbers and how difficult it can actually be to show that numbers are irrational (as we'll discuss below). Continued fractions, though, seem to be a more universal way out. We've already shown how $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational, but the actual proof is quite unique; we didn't use any of the characteristics of irrational numbers. But then we showed it was irrational again purely from its continued fraction, and that almost completely streamlined the proof to not only be direct, but essentially shorten the proof to one line: just show the continued fraction.

Before we go onto some of the more modern proofs $\pi$ is irrational, we're now somewhat familiar with continued fractions, so let's look at J. H. Lambert's (1761) original proof using them.

Theorem: $\pi$ is irrational.

Proof: I'm adapting the proof found on this Stack Exchange post, as it only uses what's necessary. For some more rigor, the Wikipedia page or this paper provide good details.

There are a few steps we'll take along the way.

Step 1: A continued fraction for $\tan(x)$.

This is by far the most tedious step, and I'll only sketch it out for actually how annoying it is. The way to derive it is to essentially consider the quotient of the power series for $\sin(x)$ and $\cos(x)$.

We'll now do a series of manipulations on this last fraction:

Let's look at the new sub-fraction of power series we have in the denominator. We'll now add and subtract the denominator of the sub-fraction as a special form of 0 to its numerator:

Combining the terms in red:

So, currently, we have

We can then continue to play the same game and adding and subtracting the denominator of our sub-fraction to its numerator:

We multiplied them by 3 to clear the units. Combining the terms in red again:

So then our expansion is

If we continue doing this, we see the pattern

Obviously, this isn't fully rigorous as we're playing with infinite series pretty carelessly, so see the above links for more details.

Step 2: A condition for irrationality.

Lemma: For a continued fraction

assume that $1 + a_n \leq b_n$. If $1+a_n < b_n$ infinitely often, then the fraction is irrational.

Proof: For contradiction, say it is rational.

The conditions $1 + a_n \leq b_n$ and $1+a_n < b_n$ infinitely often ensure that our continued fraction is between 0 and 1 (analyze the convergents), so we have $\lambda_1 < \lambda_0$. To make our life simpler, let's call a lower portion of the fraction $\rho_1$:

Then we have

So $\rho_1 = \frac{\lambda_2}{\lambda_1}$ is rational. But also, since $\rho_1$ is essentially the same "type" of continued fraction as the original, it too is between 0 and 1. Hence $\rho_1 < 1$ and therefore $\lambda_2 < \lambda_1$. We can keep repeating this process, producing a sequence of strictly descending positive integers $\cdots < \lambda_2 < \lambda_1 < \lambda_0$. But clearly this is impossible! So our continued fraction is irrational. $\ \blacksquare$

Step 3: Showing $\pi$ is irrational.

Say $\pi$ is rational. Then $\frac{\pi}{4} = \frac{a}{b}$ is also rational, and $\tan(\frac{\pi}{4}) = 1$. But we also have our continued fraction for $\tan(x)$ :

But clearly, $a^2$ is constant, so for a large enough $n$, we'll have $1 + a^2 < nb$. So at some point, we'll have a sub-fraction

that satisfies our Step 2 claim, and hence is irrational. If that subfraction is irrational, then clearly the whole fraction is irrational (just by thinking about how that continued fraction would collapse and simplify up). But clearly $\tan(\frac{\pi}{4}) = 1$ is rational. Contradiction!

So it must be that $\pi$ is irrational.

In case you were interested, since we spent all that time with approximation theorems from before, it's interesting to note that for all integers $p,q$ we have

so $\pi$ gets pretty close to some rational numbers (as we've seen with our convergents before), but it's interesting seeing the lower bound given. As always, paper attached.

The Simpler Irrationality Proofs

This proof is important for its history alone: it was the first sound proof that $\pi$ is irrational. In fact, $e$ was also first proven irrational in a similar way (Euler, 1737) by writing out the continued fraction for $e$ and showing it was infinite.

But Fourier had a much better proof that $e$ is irrational:

Claim: $e$ is irrational.

Proof: Suppose $e = \frac{a}{N}$ was rational. Now consider $e\cdot N!$ which is clearly an integer by assuming $e = \frac{a}{N}$. We can evaluate this using the series expansion $e = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{1}{k!}$.

Now the terms in blue clearly add to an integer. But the parts in red:

We bounded the red series by a geometric series, and were able to show that it must be less than 1. But that means the series in red is not an integer. Therein lies our contradiction: if we assume $e$ is rational, we have $e \cdot N!$ must be an integer, but the series expansion for $e$ would suggest that it's not.

Continued fractions are still useful today, but for irrationality proofs, the above is so much more attractive compared to finding infinite continued fractions. Which makes me want to think that Lambert's proof that $\pi$ is irrational—albeit important—is an unwieldy relic to what else is there.

Claim: $\pi$ is irrational.

I. Niven's (1947) proof that $\pi$ is irrational is actually quite short, and only relies on some calculus and a helper function. Notably, the key fact that it relies on is that $\pi$ is the smallest positive 0 of $\sin(x)$.

Lemma: For all $n \geq 1$, consider the function

Then the following are true:

- $f(x)$ is a polynomial of the form $\frac{1}{n!} \sum_{k=n}^{2n} c_k x^k$ with integer coefficients $c_k$

- For $0 < x < \frac{a}{b}$, we have $0 < f(x) < \frac{1}{n!}$

- For all $k \geq 0$, the derivatives $f^{(k)}(0)$ and $f^{(k)}(\frac{a}{b})$ are integers.

Proof: Claims 1. and 2. are straightforward (consider binomial expansion, and the factors in the numerator). For 3., note by 1., we've shown $f(x)$ is a polynomial consisting of terms with degree between $n$ and $2n$. So $f^{(k)}(0) = 0$ unless $n\leq k\leq 2n$. When $n\leq k\leq 2n$, then $f^{(k)}(0) = \frac{k!}{n!} c_k$. Since $k \geq n$ and $c_k$ is an integer, then $\frac{k!}{n!} c_k$ is also an integer. By the symmetry in $f(x) = f(\frac{a}{b}-x)$, we get $f^{(k)}(x) = (-1)^k f^{(k)}(\frac{a}{b}-x)$. Therefore $f^{(k)}(\frac{a}{b}) = (-1)^k f^{(k)}(0)$ is also an integer. $ \ \blacksquare$

Now we can prove $\pi$ is irrational.

Proof: Assume $\pi = \frac{a}{b}$ is rational, and consider $f(x)$ from the above lemma. Now define the new function

If we take the derivative of this, we find

$F''(x)$ looks a lot like $F(x)$. In particular, we have this relation:

Note this holds precisely because $f^{(2n+2)}(x) = 0$. With this in mind, we can see that the following derivative is

Thus, if we integrate the righthand-side,

By part 3. of our lemma $f^{(k)}(\pi)$ and $f^{(k)}(0)$ are integers for all $k$, so $F(\pi) + F(0)$ is an integer.

Note now for $0<x<\pi = \frac{a}{b}$ and that $0 < \sin(x) < 1$ in this range, we have

But the RHS can be made arbitrarily small, i.e. $\frac{\pi^n a^n}{n!} < \frac{1}{\pi}$ for a big enough $n$. So we can bound our integral by

However, we claimed that $\int_{0}^{\pi} f(x)\sin(x) = F(\pi) + F(0)$ is an integer. But there is no integer between 0 and 1! So our assumption that $\pi$ was rational must be wrong, and so $\pi$ is irrational.

This proof is "simpler" in that the mathematical machinery required is relatively low-level. It might be that the actual contradiction we were looking for is less obvious, but we didn't have to prove that many obscure, auxilliary lemmas like we did with continued fractions in Lambert's proof.

Proofs from THE BOOK generalizes this proof strategy to show a few more interesting irrationality results.

Lemma: For all $n \geq 1$, consider the function

Then the following are true:

- $f(x)$ is a polynomial of the form $\frac{1}{n!} \sum_{k=n}^{2n} c_k x^k$ with integer coefficients $c_k$

- For $0 < x < 1$, we have $0 < f(x) < \frac{1}{n!}$

- For all $k \geq 0$, the derivatives $f^{(k)}(0)$ and $f^{(k)}(1)$ are integers.

Proof follows exactly as you'd expect from before.

Theorem: $e^r$ is irrational for all rational $r \neq 0$.

Proof: We can reduce this by considering $e^p$ is irratraional for all integers $p$, since if $e^{\frac{p}{q}}$ was rational, then $(e^{\frac{p}{q}})^q = e^p$ would also be rational. The key idea here is using that $\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}x} e^x = e^x$.

Let $f(x) = \frac{x^n(1-x)^n}{n!}$ refer to the one from the lemma above. As usual, assume the contrary and that $e^p = \frac{a}{b}$. Now consider the new function

This looks familiar to the one Niven used to show $\pi$ is irrational. Taking its derivative:

Hence, we get the relation

Now we take the derivative of a particularly nice function:

Integrating, we then get

Recalling that $e^p = \frac{a}{b}$, we conclude that

is an integer. As before, we can bound this integral from above:

We get the last inequality by just taking a large enough $n$. There are no integers between 0 and 1, giving us our contradiction and completing the proof.

Open Questions and More Strangeness

Irrational Powers

But not much about irrationals are that well understood. It's quite simple to show that combining an rational with another rational number via addition, multiplication, division, and subtraction, only results in more rational numbers. Further, it's not too bad to show that combinations in the same way with an irrational and rational only lead to more irrationals. But combining irrationals are a little strange: obviously $(1 - \sqrt{2}) + \sqrt{2} = 1$ is the sum of two irrational numbers that result in a rational. You can even find two irrational numbers $a,b$ such that $a^b$ is rational.

Claim: There exists irrational numbers $a$ and $b$ such that $a^b$ is rational.

Proof: We know that $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational, so consider the number $\sqrt{2}^\sqrt{2}$. If this is rational, we're done. If this is irrational, then consider the number $(\sqrt{2}^\sqrt{2})^\sqrt{2} = \sqrt{2}^2 = 2$, which is rational, and hence we are done.

In fact, it is possible to show for a lot of positive rational numbers $r$, there exists an irrational $a$ such that $a^a = r$.

Theorem: For every rational number $r \in \left( (1/e)^{1/e}, \infty \right)$, either $r = a^a$ for an irrational $a$, or $r \in \{1, 4, 27, 256, \cdots, n^n, \cdots \}$.

Proof: Consider the function $f(x) = x^x$ on the interval $I = (1/e, \infty)$. $f(x)$ is continuous on $I$, since it is differentiable, and injective as it is monotonic (check derivative is strictly positive), so $f(I) = \left( (1/e)^{1/e}, \infty \right)$. So given a rational $r \in f(I)$, let $a \in I$ be the corresponding value such that $a^a = r$.

We'll now go and prove the contrapositive: if $a$ is rational and not an integer, then $a^a$ is irrational. In other words, if $r = \frac{p}{q}$, and $a = \frac{n}{m}$ are in lowest terms i.e. $\gcd(p,q) = \gcd(n,m) = 1$, and

then $m = 1$ and $a$ must be an integer. So, for a contradiction, assume that $m > 1$. Rearranging our equation, we get that

Since $\gcd(p,q) = 1$, a prime divides the factor $q^m$ on the left-hand side if and only if it divides the factor $m^n$ on the right-hand side. So $q^m = m^n$. Since $m > 1$, we can write $q = \alpha^i k$ and $m = \alpha^j l$ for some prime $\alpha$ and integers $k,l$. Since $q^m = m^n$, we must also have $im = jn$ for the exponent of $\alpha$ to match. Thus $i(\alpha^j l) = jn$, and $\alpha^j$ divides $jn$.

But $\gcd(m,n) = 1$, and $\alpha^j$ is a factor of $m$, hence $\alpha^j$ divides $j$. So, $\alpha^j \leq j$. Since $\alpha$ is a prime, $2 \leq \alpha$, and so $2^j \leq j$. But it can easily be shown that $2^j > j$ for all integers $j$, giving us the contradiction.

Transcendental Numbers

$\pi$ being irrational is a well-known fact among everyone. A more surprising fact to more mathematically inclined is the fact that $\pi$ is transcendental.

Not all irrational numbers are equal. $\sqrt{2}$ is, in some ways, defined by the fact that it is the (positive) root to $x^2 - 2 = 0$. Despite being, well, just a number that seems to exist as its own object, $\sqrt{2}$ has a decidedly algebraic quality to it which allows us to precisely specify it in much simpler terms (i.e. integers and arithmetic). Lots of numbers can be characterized as solutions to polynomials. Even imaginary numbers, which many find difficult to grasp, can be simply defined in terms of simple polynomials: $\pm i$ are the solutions to $x^2 + 1 = 0$.

But not every number can be defined via a polynomial. In fact, it's not too hard to show that there are only countably many of these algebraic numbers, so certainly the unconutable $\mathbb{R}$ contains some non-algebraic or transcendental numbers. Two of which we are already familiar with: $\pi$ and $e$.

Proving numbers, especially $\pi$ and $e$, are not straightforward by any means, and simple statements of them were huge discussion points throughout math's history (see Hilbert's 7th Problem), resulting in major theorems like the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem. The first number to be discovered to be transcendental was one by Liouville, aptly called Liouville's constant:

and you can find a proof of its transcendence here.

Maybe we'll come back to all this later, but for now, we've done enough and can save it for another day.