What shape has the largest area to perimeter ratio?

Some might have a guess, or an intuitition for what the answer should be, but it's a surprisingly difficult question to pin down as a proof. In fact, a rigorous proof wasn't given until around 1840 (J. Steiner)!

Some Observations

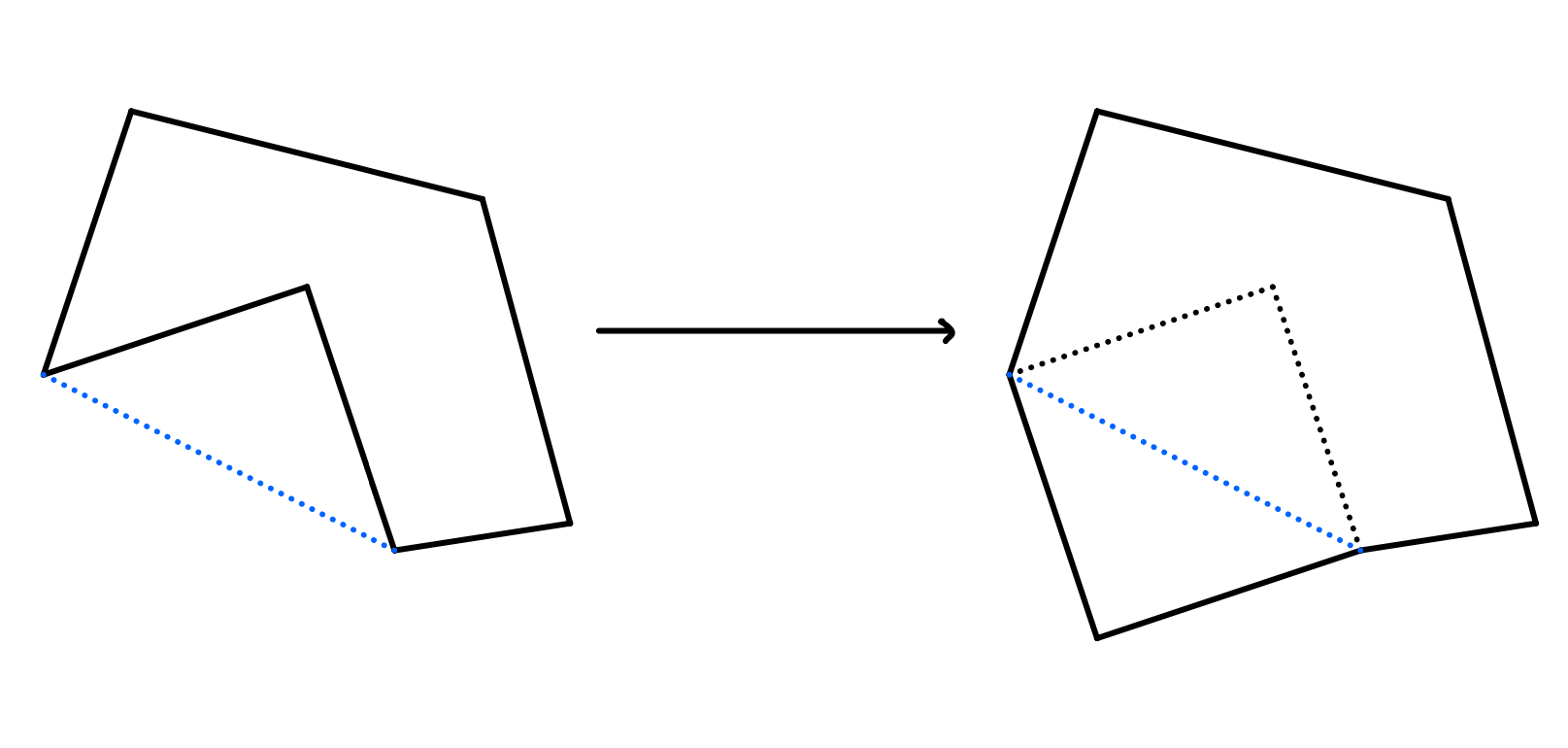

There are some facts about our ideal shape we can observe quickly. First, it has to be convex_**. For if our shape was concave, we could always add more area with simple reflections.

We can get free area by reflecting over the blue line.

This can also be seen to work for not just polygons but curves as well, where instead of reflecting over vertices we can reflect over tangents.

Concavity is wasted. Credit: Wikipedia

Further, in a similar argument, there has to be a type of perimeter-symmetry to our shape. For any way of dividing our shape into two equal perimeters, the areas enclosed by this dividing line must be equal. If they were not, one half would be bigger than the other, and we could just reflect that bigger half over the line to get a shape with the same perimeter but greater area (as we would have two copies of the bigger half glued together, as opposed to the bigger half attached to the smaller half).

If area 1 was bigger than area 2, we can just replace area 2 with a reflection of area 1. We can then smooth out any cocavities the same way we did before.

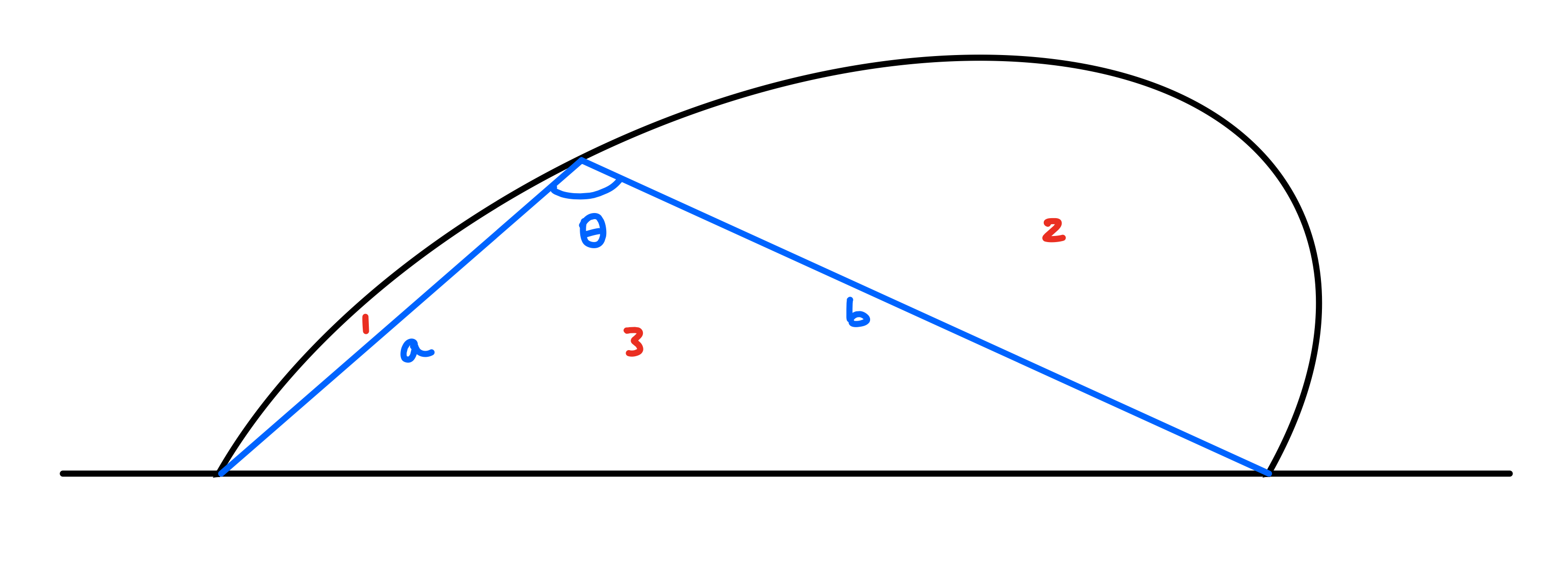

This then also gives us a way to half our problem. Literally: instead of looking for the curve that encloses the most area for the same perimeter, we can instead look for the arc that encloses the most area with its endpoints connected by a fixed straight line. Then we can just reflect over it and we're good. So let's look at an arc.

We can divide the area of our arc into 3 sections with an inscribed triangle.

Is there any way we can increase the area of this arc? With the above diagram, we have divided the area into 3 sections. Since we want to keep the arc's perimeter fixed, we can't really affect areas 1 and 2. But 3 we can maximize easily. For a triangle with 2 fixed side-lengths and the angle in between them, the area of the triangle is $ab\sin\theta$, which is maximized when $\theta$ is a right angle. So, we can increase the arc's overall area by picking a point along the curve, and having it such that it always forms a right triangle with the base of the arc.

So, to maximize the area of the arc, we want this to be true for any point picked along the curve. What curve is defined by forming a right triangle with its base at every point? It's a semi-circle! By fixing the base-length as well as the right angle restriction, it happens to also fix all radial lines from the mid point of the base. So finally reflecting back over the line as our second observation suggests, the shape that encloses the most area for a given perimeter is a circle.

…that is if such a shape exists. What we have really shown is that IF there is a shape that encloses the most area for a given arc length, THEN it is a circle. We have not necessarily shown that there is a shape. Intuitively, it seems a bit frivolous to worry about it since it just makes sense that there is only so much you can do to spread a curve out, but it is worth taking a second to do so. For, if the problem was, "What shape encloses the least area for a given perimeter?", there is no such shape we can give. But this is a nit-picking detail that can be shown with not much difficulty using some calculus and limiting processes, but is worth keeping in mind.

Some might know the answer off the top of their head, and some might be able to guess, but the answer is unsurprisingly a circle. And we see that this is realized all throughout nature. Bubbles are circular since for a fixed amount of gas (i.e. volume), the sphere requires the least surface area to accomodate it (and therefore put the least amount of stress on the bubble). Rain drops, too, would be perfectly spherical if not for gravity.

The Analytic Approach

With more robust tools, we can prove this more directly—albeit in a more overkill way. Our problem of finding the greatest area per perimeter is a byproduct of the isoperimetric inequality: for a given perimeter/arc length of a curve $L$ that encloses an area $A$, then $4 \pi A \leq L^2$. The proof isn't long, but requires some less accessible calculus machinery. The below is adapted from Erhard Schmidt's 1938 proof.

PROOF: Let's parameterize a general simple closed curve $C$ (i.e. does not cross itself and ends where it starts), say $c(t) = (x(t),y(t))$. Since we care about arc length, we will parameterize $c(t)$ with arc length i.e. $\forall t \ |c'(t)| = 1$ so that $c(L)$ is our end point of the curve. Now as it is a simple closed curve, $y(t)$ must be bounded as continuous functions on a bounded interval are bounded. So we can enclose our curve by two parallel lines, say, $l$ and $l'$ that meet the curve $c(t)$ at say $t=0, t_{l}$.

Then, the area bounded by our curve $C$ is $A = \int_C x \ dy = \int_0^L x(t)y'(t) \ dt$ by Green's theorem.

Now we can construct an "approximate" circle to our curve, that is parameterized by $r(t) = (x(t), z(t))$ and is also tangent to $l$ and $l'$ (note that they are parameterized by the same x-vector). Call the radius of the circle $R$ and let its center be the origin of our coordinate system. Using our previous parameters, we will further fix this circle by

to ensure it lies in the $l$ and $l'$ and is, well, a circle. Then, the area bounded by our circle is $\pi R^2 = - \int_\textrm{circle} y \ dx = - \int_0^L z(t)x'(t) \ dt$.

Adding our areas together, we get,

as $x^2 + z^2 = R^2$ and $y'^2 + x'^2 = 1$. The first inequality is by the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality (AM-GM), and the second one is by the Cauchy-Shwarz inequality applied to $(x, z)$ and $(y',x')$. So putting it all together, $2R\sqrt{A\pi} \leq LR$, or $4\pi A \leq L^2$.

To get equality, we need to satisfy the first and last inequalities. To get equality in AM-GM, we need $A = \pi R^2$ and thus $L = 2\pi R$. To get equality in Cauchy-Scharwz, we want our vectors to be parallel i.e. $\frac{z}{x} = \frac{-x'}{y'} \rightarrow zy = -xx'$. Substituting this into

from above nets that $x = \pm Ry'$ and $y = \pm Rx'$, or in other words by squaring and summing both equations, $x^2 + y^2 = R^2$, which is precisely the definition of a circle.

So?

This problem generalizes to higher dimensions with higher dimension balls being the solution. But what I find most ineteresting is how quickly this problem changes with a slight tweak. We now know for sure circles are the best shape for a single container; an orange grows in the way for me to have the most amount of fruit in that single orange. But what if I had multiple oranges? Circles are awful to pack together as unlike, say, squares that nestle nicely together, circles leave so much extra room.

Even when optimally placed here, still about 10% of area is left uncovered.

So, if we wanted to create the optimal shape for stacking together using the least materials, what shape would that be? Clearly the answer is not a circle since it doesn't stack efficiently, and we have at the very least a square as our starting point. It turns out the answer, as nature has found its answer through bees, are hexagons. Perhaps another day we will go through the proof, but Thomas Hale's original proof of this Honeycomb conjecture is dense enough to leave alone for now.

What is even more interesting, is that unlike the isoperimetric problem from above, the 3D Honeycomb conjecture is still unsolved: what is the shape with the best area/surface area ratio to tesselate space? The Weaire-Phelan structure gives a non-obvious polyhedron that's the current record holder for known shapes, but it has not been proven to be the best.

The study of these minimal surfaces all tend to follow similar problems like the ones above, and just how deceptively difficult they are are what make them so interesting. Inspiration from physics and observed phenomena in nature are so helpful to guide us towards intuitions, the rigorous proof math demands is so often buried by our own self-defeating intuitions. If you're interested in more like this, I'd suggest skimming over one of our previous discussions on the calculus of variations.